Transfer Pricing Guide

Corporate Tax Guide | CTGTP1

October 2023

Contents

3. Transfer Pricing at a glance

4. Transfer Pricing Principles and Fundamentals

5. Application of the Arm’s Length Principle

5.2. Step 2: Selection of the most appropriate Transfer Pricing method

6. Transfer Pricing Documentation

6.2. Objectives of Transfer Pricing documentation

6.3. Contemporaneous Transfer Pricing documentation

6.4. Summary of the UAE Transfer Pricing documentation requirements

6.5. General Transfer Pricing disclosure form

7. Special Considerations for Specific Cases

7.2.2. Determining whether an intra-group service has been rendered

7.2.3. Determining the arm’s length charge for intra-group services

7.3.2. Identifying intangibles (Types of intangibles)

7.3.3. Applying the Arm’s Length Principle with respect to intangibles

7.4. Cost Contribution Arrangements

7.4.2. Types of Cost Contribution Arrangements

7.4.3. Applying the Arm’s Length Principle to a Cost Contribution Arrangement

Glossary

Definitions

Arm's Length Price | : | The price determined for a specific business transaction in accordance with the Arm’s Length Principle. |

Arm's Length Principle | : | The international standard that the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries and many other jurisdictions have agreed to use for determining transfer prices for tax purposes. The principle is set forth in Article 9 of the OECD Model Tax Convention as follows: where conditions are made or imposed between the two enterprises in their commercial or financial relations which differ from those which would be made between independent enterprises, then any profits which would, but for those conditions, have accrued to one of the enterprises, but, by reason of those conditions, have not so accrued, may be included in the profits of that enterprise and taxed accordingly. (OECD, 2017) |

Business | : | Any activity conducted regularly, on an ongoing and independent basis by any Person and in any location, such as industrial, commercial, agricultural, vocational, professional, service or excavation activities or any other activity related to the use of tangible or intangible properties. |

Business Activity | : | Any transaction or activity, or series of transactions or series of activities conducted by a Person in the course of its Business. |

Business Restructuring | : | A cross-border or domestic reorganisation of the commercial or financial relations between Related Parties or Connected Persons, including the termination or substantial renegotiation of existing arrangements. |

Comparable Uncontrolled Price Method | : | A Transfer Pricing method that compares the price for property or services transferred in a Controlled Transaction to the price charged for property or services transferred in a Comparable Uncontrolled Transaction in comparable circumstances. |

Comparable Uncontrolled Transaction | : | A transaction between two independent parties that is comparable to the transaction under examination (“Controlled Transaction”). It can be either a comparable transaction between one party to the Controlled Transaction and an independent party (“internal comparable”) or between two independent parties, neither of which is a party to the Controlled Transaction (“external comparable”). |

Connected Person | : | Any Person affiliated with a Taxable Person as determined in Clause 2 of Article 36 of the Corporate Tax Law. |

Consolidated Financial Statements | : | The financial statements of the MNE Group in which the assets, liabilities, revenues, expenses, and cash flows of the Ultimate Parent Entity and Constituent Entities are presented as those of a single economic entity. |

Constituent Company | : | Means under Article 1 of the Cabinet Resolution No. 44 of 2020 any of the following:

|

Control | : | The direction and influence over one Person by another Person in accordance with Clause 2 of Article 35 of the Corporate Tax Law. |

Controlled Transactions | : | Transactions or arrangements between two parties that are Related Parties or Connected Persons. |

Corporate Tax | : | The tax regime imposed by the Corporate Tax Law on juridical persons and Business income. |

Corporate Tax Law | : | Federal Decree-Law No. 47 of 2022 on the Taxation of Corporations and Businesses. |

Cost Plus Method | : | A Transfer Pricing method using the costs incurred by the supplier of goods (or services) in a Controlled Transaction. An appropriate cost-plus mark-up is added to this cost, to make an appropriate profit in light of the functions performed (taking into account assets used and risks assumed) and the market conditions. The amount after adding the cost-plus mark-up to the above costs may be regarded as an Arm’s Length Price of the original Controlled Transaction. |

Country-by-Country Report | : | A report that declares annually the details of each tax jurisdiction in which a Multinational Enterprise Group (“MNE”) does business. This includes the amount of revenue, profit before income tax and income tax paid and accrued. It also requires MNEs to report their number of employees, stated capital, retained earnings and tangible assets in each tax jurisdiction. Finally, it requires MNEs to identify each entity within the group doing business in a particular tax jurisdiction and to provide an indication of the business activities each entity engages in. |

Country-by-Country Reporting | : | An obligation to submit a Country-by-Country Report as introduced by Action 13 of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (“BEPS”) initiative led by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (“OECD”) and the Group of Twenty (“G20”) industrialised nations. This is enforced in the UAE via Cabinet Resolution No. 44 of 2020 on Organising Reports submitted by Multinational Companies. |

Double Taxation Agreement | : | An international agreement signed by two or more countries for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion on income and capital. |

Exempt Person | : | A Person exempt from Corporate Tax under Article 4 of the Corporate Tax Law. |

Fiscal Year | : | The annual accounting period in respect to which the Reporting Entity prepares the financial statements. |

Free Zone | : | A designated and defined geographic area within the UAE that is specified in a decision issued by the Cabinet at the suggestion of the Minister. |

Free Zone Person | : | A juridical person incorporated, established or otherwise registered in a Free Zone, including a branch of a Non-Resident Person registered in a Free Zone. |

Federal Tax Authority | : | The authority in charge of administration, collection and enforcement of federal taxes in the UAE. |

Functional Analysis | : | The analysis aimed at identifying the economically significant activities and responsibilities undertaken, assets used or contributed, and risks assumed by the parties to the transactions. |

Group | : | Two or more companies related through ownership or control in accordance with Article 1 of the Cabinet Resolution No. 44 of 2020, such that it either is required to prepare Consolidated Financial Statements for the purposes of preparing financial reports under the applicable accounting principles or would be so required if the equity interests in any of the companies were traded on a public securities exchange. |

Guide | : | Refers to the present Transfer Pricing Guide published by the FTA. |

Local File | : | A Transfer Pricing documentation which contains detailed information on all Controlled Transactions of the Taxable Person and other information about the Business of the Taxable Person. |

Market Value | : | The price which could be agreed in an arm’s-length free market transaction between Persons who are not Related Parties or Connected Persons in similar circumstances. |

Master File | : | A Transfer Pricing documentation which provides an overview of the MNE Group Business, including the nature of its global Business operations, its overall Transfer Pricing policies, and its global allocation of income and economic activity in order to assist tax administrations in evaluating the presence of significant Transfer Pricing risk. |

Minister | : | Minister of Finance. |

MNE Group | : | Any Group that meets the criteria prescribed in Article 1 of Cabinet Resolution No. 44 of 2020:

|

OECD Model Convention | : | The 2017 version of the OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and Capital. |

Natural Person | : | Individual human being (distinct from a juridical person). |

Non-Resident Person | : | The Taxable Person specified in Article 11(4) of the Corporate Tax Law. |

OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines | : | The 2022 version of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations. |

Person | : | Any Natural Person or Juridical Person. |

Profit Split Method | : | A Transfer Pricing method that identifies the relevant profits to be split for the Related Parties or Connected Persons from a Controlled Transaction (or Controlled Transactions that can be aggregated) and then splits those profits between the Related Parties or Connected Persons on an economically valid basis that approximates the division of profits that would have been agreed at arm’s length. |

Recognised Stock Exchange | : | Any stock exchange established in the UAE that is licensed and regulated by the relevant competent authority, or any stock exchange established outside the UAE of equal standing. |

Related Party | : | Any Person associated with a Taxable Person as determined in Article 35(1) of the Corporate Tax Law. |

Reporting Entity | : | The Ultimate Parent Entity of an MNE Group in accordance with Article 1 of the Cabinet Resolution No. 44 of 2020 whose tax residence is located in the UAE and is required to submit a Country-by-Country Report on behalf of the MNE Group. |

Resale Price Margin | : | The margin representing the amount out of which a reseller would seek to cover its selling and other operating expenses and, in the light of the functions performed (taking into account assets used and risks assumed), make an appropriate profit. |

Resale Price Method | : | A Transfer Pricing method based on the price at which a product that has been purchased from a Related Party is resold to an Independent Party. The resale price is reduced by the Resale Price Margin. What is left after subtracting the Resale Price Margin can be regarded, after adjustment for other costs associated with the purchase of the product (for example, custom duties), as an Arm’s Length Price of the original transfer of property between the Related Parties or Connected Persons. |

Resident Person | : | The Taxable Person specified in Article 11(3) of the Corporate Tax Law. |

Tax Period | : | The period for which a Tax Return is required to be filed. |

Tax Return | : | Information filed with the FTA for Corporate Tax purposes in the form and manner as prescribed by the FTA, including any schedule or attachment thereto, and any amendment thereof. |

Taxable Income | : | The income that is subject to Corporate Tax under the Corporate Tax Law. |

Taxable Person | : | A Person that is subject to Corporate Tax under the Corporate Tax Law. |

Transactional Net Margin Method | : | A Transfer Pricing method that examines the net profit margin relative to an appropriate base (for example, costs, sales, assets) that a Taxable Person realises from a Controlled Transaction (or transactions that are appropriate to be aggregated). |

Transfer Pricing | : | Rules on setting of arm’s length prices for Controlled Transactions, including but not limited to the provision or receipt of goods, services, loans and intangibles. |

Ultimate Parent Entity | : | The Constituent Company in the MNE Group that meets the following criteria stated in Article 1 of the Cabinet Resolution No. 44 of 2020:

|

Acronyms and Abbreviations

AED | : | United Arab Emirates Dirham |

BEPS | : | Base Erosion and Profit Shifting |

CbCR | : | Country-by-Country Reporting |

CCA | : | Cost Contribution Arrangement |

CPM | : | Cost Plus Method |

CUP | : | Comparable Uncontrolled Price |

DEMPE | : | Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection and Exploitation |

DTA | : | Double Taxation Agreement |

FTA | : | Federal Tax Authority |

MNE | : | Multinational Enterprise |

OECD | : | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

PE | : | Permanent Establishment |

PSM | : | Profit Split Method |

RPM | : | Resale Price Method |

R&D | : | Research and Development |

TNMM | : | Transactional Net Margin Method |

TP | : | Transfer Pricing |

UAE | : | United Arab Emirates |

Introduction

Overview

Federal Decree-Law No. 47 of 2022 on the Taxation of Corporations and Businesses (“Corporate Tax Law”) was issued on 3 October 2022 and was published in Issue #737 of the Official Gazette of the United Arab Emirates (“UAE”) on 10 October 2022.

The Corporate Tax Law provides the legislative basis for imposing a federal tax on corporations and Business profits (“Corporate Tax”) in the UAE.

The provisions of the Corporate Tax Law shall apply to Tax Periods commencing on or after 1 June 2023.

Purpose of this guide

This guide is designed to provide general guidance on the Transfer Pricing regime in the UAE with a view to making the provisions of the Transfer Pricing regulations as understandable as possible to readers. It provides readers with:

An overview of the Transfer Pricing rules and procedures, including the determination of the Related Party transactions, whether transactions are done on an Arm’s Length basis, and other related compliance requirements including Transfer Pricing documentation; and

Assistance with the most common questions businesses might have to reduce uncertainties for Taxable Persons in relation to the implementation and application of the Transfer Pricing provisions of the Corporate Tax Law.

Who should read this guide?

This guide should be read by any juridical or natural person who wants to know more about the Transfer Pricing regime in the UAE. It is intended to be read in conjunction with the Corporate Tax Law, the implementing decisions and other relevant guidance published by the FTA.

How to use this guide

The relevant articles of the Corporate Tax Law and the implementing decisions are indicated in each section of the guide.

It is recommended that the guide is read in its entirety to provide a complete understanding of the definitions and interactions of the different rules. Further guidance on some of the areas covered in this guide can be found in other topic- specific guides.

In some instances, simple examples are used to illustrate how key elements of the Transfer Pricing regime applies to juridical and natural persons. The examples in the guide:

Show how these elements operate in isolation and do not show the interactions with other provisions of the Transfer Pricing regime that may occur. They do not, and are not intended to, cover the full facts of the hypothetical scenarios used nor all aspects of the Transfer Pricing regime, and should not be relied upon for legal or tax advice purposes; and

Are only meant for providing the readers with general information on the subject matter of this guide. They are exclusively intended to explain the rules related to the subject matter of this guide and do not relate at all to the tax or legal position of any specific juridical or natural person.

Legislative references

In this guide, the following legislation will be referred to as follows:

Federal Decree-Law No. 47 of 2022 on the Taxation of Corporations and Businesses is referred to as “Corporate Tax Law”;

Federal Law No. 5 of 1985 on the Civil Transactions Law of the United Arab Emirates is referred to as “Federal Law No. 5 of 1985”.

Cabinet Resolution No. 44 of 2020 on Organising Reports Submitted by Multinational Companies as “Cabinet Resolution No. 44 of 2020”; and

Ministerial Decision No. 97 of 2023 on Requirements for Maintaining Transfer Pricing Documentation for the Purposes of Federal Decree-Law No. 47 of 2022 on the Taxation of Corporations and Businesses is referred to as “Ministerial Decision No. 97 of 2023”. [1]

Status of this guide

This guidance is not a legally binding document, but is intended to provide assistance in understanding the provisions relating to the Corporate Tax regime in the UAE. The information provided in this guide should not be interpreted as legal or tax advice. It is not meant to be comprehensive and does not provide a definitive answer in every case. It is based on the legislation as it stood when the guide was published. Each person’s own specific circumstances should be considered.

The Corporate Tax Law, the implementing decisions and the guidance materials referred to in this document will set out the principles and rules that govern the application of Corporate Tax. Nothing in this publication modifies or is intended to modify the requirements of any legislation.

This Guide takes into consideration the guidance provided by the January 2022 OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations (“OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines”). However, Taxable Persons should rely primarily on the Corporate Tax Law, the Ministerial Decision No. 97 of 2023, and this Guide for Transfer Pricing matters involving the UAE. This Guide should be primary source of guidance for Transfer Pricing related matters prevailing over international standards, however, if a certain aspect is not covered, taxpayers are encouraged to refer to OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines if an issue is not addressed herein. Furthermore, the following reports have been considered:

OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations of 2022, referred to as “OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines”; [2]

OECD Transfer Pricing Documentation and Country-by-Country Reporting, Action 13 - 2015 Final Report, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, referred to as ‘BEPS Action 13’;

OECD 2010 report on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments issued by the OECD for further guidance; [3]

OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and Capital of 2017, referred to as “OECD Model Convention”; [4]and

OECD 2018 Additional Guidance on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments. [5]

The FTA reiterates the need for keeping supporting documentation to justify the application of the chosen Transfer Pricing method or of the relevant rules for the specific taxable person.

This document is subject to change without notice.

Transfer Pricing at a glance

Transfer Pricing refers to the pricing of transactions between Related Parties or Connected Persons, and has become increasingly important due to globalisation and cross border trade activities by enterprises. The significance of Transfer Pricing has resulted in the introduction of Transfer Pricing legislation in many countries. Organisations such as the OECD and the United Nations (“UN”) have published detailed Transfer Pricing guidelines proposing how to govern transactions between Related Parties from a tax perspective and recommended documentation standards.

Whilst the Transfer Pricing policy of a Group may not have an overall impact on that Group’s consolidated profits, the pricing of its Controlled Transactions can lead to the underpayment of tax in one or more jurisdiction. In particular, transactions and arrangements between Group entities can be used to artificially shift profits from Group entities in higher tax jurisdictions to lower tax jurisdictions, and from high-tax entities to low or no-tax entities, resulting in an overall lower tax burden for the Group.

To prevent such price distortions, tax administrations may assess the prices of transactions between Related Parties or Connected Persons to verify if the transactions have been priced at Market Value. Tax administrations may perform a Transfer Pricing adjustment if a transaction is not found to be reflective of the Market Value or Arm’s Length Price.

Such adjustments can result in double taxation for MNE Groups operating in multiple jurisdictions. However, the Mutual Agreement Procedure (“MAP”) article in Double Tax Agreements allows competent authorities in partner jurisdictions to interact with the intent to resolve international tax disputes involving cases of double taxation where the same profits have been taxed in two jurisdictions. The objective of the MAP process is to negotiate an arm’s length position that is acceptable to both competent authorities and seek to avoid double taxation. This procedure will be further detailed in separate guidance.

To reduce the risk of audits and double taxation, when transacting with Related Parties or Connected Persons, Taxable Persons should ensure the transfer price between the parties is at arm’s length (i.e. as if they were independent parties negotiating freely) and maintain supporting Transfer Pricing documentation.

Transfer Pricing rules in the UAE apply not only to MNE Groups, but also to any transactions and arrangements with Related Parties or Connected Persons in domestic groups. All these transactions need to meet the arm’s length principle. In addition, transactions above the materiality threshold to be set through an FTA Decision [6] will need to be disclosed for the purposes of Transfer Pricing (“TP”) Documentation. [G1]

Transfer Pricing Principles and Fundamentals

Overview

The purpose of this section is to introduce the concept of Transfer Pricing as well as clarify the Persons and transactions in scope for the application of the Arm’s Length Principle in the UAE.

What is Transfer Pricing

Transfer Pricing is primarily a tax concept, but which also has important accounting and risk-related implications. It refers to the pricing of transactions or arrangements between Related Parties or Connected Persons that are influenced by the relationship between the transacting parties. Transactions that occur between Related Parties or Connected Persons may include but are not limited to the trade of services, tangible goods, intangibles, financial transactions as well as certain transactions involving a Permanent Establishment (PE).

When independent parties transact with each other, the conditions of their commercial and financial relations (for example, the price of goods transferred, or services provided and the conditions of the transfer or provision) ordinarily are determined by market forces and negotiations. On the other hand, Related Parties or Connected Persons may not be subject to the same external market forces in their dealings and may be influenced by the relationship between the parties involved. As a result, Related Parties or Connected Persons can use non-arm’s length pricing in their Controlled Transactions in order to alter the profits reported in the relevant jurisdiction or entity and thus optimise the resulting tax liabilities.

The internationally recognised standard in pricing such transactions is the Arm’s Length Principle, which requires that Controlled Transactions be conducted at open market value as would be the case between independent parties.

Given the above, the Transfer Pricing provisions of the Corporate Tax Law and the Ministerial Decision No. 97 of 2023 were introduced to ensure that the ‘Related Parties’ and ‘Connected Persons’ are setting the conditions of their Controlled Transactions in a manner that is similar to those between independent parties in comparable circumstances.

The Arm’s Length Principle

The Arm’s Length Principle, as introduced in the UAE under Article 34 of the Corporate Tax Law, requires that transactions and arrangements between Related Parties or Connected Persons are priced as if the transactions or arrangements had occurred between independent parties under similar circumstances. It is central to the Arm’s Length Principle to consider what price two independent parties would have agreed in similar circumstances, and that this should be based, wherever possible, on direct or indirect evidence of how independent parties would have behaved.

It is important to note that the absence of a formal pricing arrangement or legal agreement between the transacting Related Parties or Connected Persons does not mean that there is no such arrangement in place. In instances where a transfer of property takes place or a service is provided without a formal arrangement or without remuneration or at remuneration below Market Value, the Arm’s Length Principle should always be applied to determine whether such a transaction or arrangement would have taken place between independent parties under similar circumstances and at what value.

The Arm’s Length Principle treats Related Parties and Connected Persons, such as for example, members of a Group, as if they were operating as separate entities rather than as inseparable parts of a single unified Business. Since the separate entity approach treats these members as if they were independent parties, attention is focused on the nature of the Controlled Transactions and on whether the conditions differ from the conditions that would be observed in Comparable Uncontrolled Transactions. Such a comparison of the Controlled Transaction(s) with Comparable Uncontrolled Transactions is named as a “comparability analysis” and is at the heart of the application of the Arm’s Length Principle (see further in Section 5).

In other words, the Corporate Tax Law requires Related Parties or Connected Persons to earn their “fair share” of profits based on the Arm’s Length Principle. Thus, after applying the Arm’s Length Principle, each Related Party or Connected Person should record operating profits in line with their respective functions, assets and risks and contributions to the value chain across the Group.

Under the Corporate Tax Law and this Guide, the Arm’s Length Principle needs to be applied with respect to domestic as well as cross-border Controlled Transactions.

Example 1: Transactions between Related Parties

AB Group is a furniture company group with two subsidiaries: Company A, a sawmill located in the UAE, and Company B, a manufacturing company located in Country B where corporate profits are taxed at 5%.

Company B purchases a ton of timber from Company A at a price of AED 15,000. The cost for Company A to produce a ton of timber is AED 15,000. The market price for a ton of timber is AED 20,000.

| Production cost | Sale price from Company A to Company B (related parties) | Market price | |

|---|---|---|---|

Company A (AED) | 15,000 | 15,000 | 20,000 |

Company A has made no profit on the sale to Company B, whereas it would have made a profit of AED 5,000 had it sold its timber to a third party, resulting in an overall decrease in profit of AED 5,000 compared to if Company B had paid under an Arm’s Length Price transaction.

Company B subsequently sells the goods manufactured using the timber to a third party for AED 30,000. Company B has decreased its cost of sales by AED 5,000 by purchasing at the internal transfer price from Company A as opposed to the market price from a third party. Hence, Company B has increased its profits by AED 5,000.

However, whilst Company A has seen a fall in its profit of AED 5,000 and Company B has seen an increase in its profit of AED 5,000, the overall impact on the Group’s earnings is nil, as both transactions occurred within the Group and related party transactions are generally eliminated while preparing consolidated financial statements.

| Sale below market price | Sale at market price | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company A | Company B | Company A | Company B | |

Profit (AED) | 0 | 15,000 | 5,000 | 10,000 |

Tax rate in jurisdiction | 9% | 5% | 9% [7] | 5% |

Tax paid (AED) | 0 | 750 | 450 | 500 |

Total tax paid (AED) | 750 | 950 | ||

Although the overall profit of the Group company has not changed, the application of Transfer Pricing and the structure of AB Company Group has resulted in total tax paid of AED 750, consisting of 0 AED for Company A and 750 AED for Company B.

Whereas if the transaction was conducted at Market Value, the total tax payable would be AED 950, comprised of AED 450 by Company A and AED 500 by Company B.

Therefore, the non-arm’s length pricing of goods transferred between Related Parties has shifted profits between jurisdictions, resulting in a tax benefit for this Group. These transactions would need to be adjusted in line with the Arm’s Length Principle and reflect the Market Value. As a consequence, the total tax payable by AB Group will increase.

Scope of the Transfer Pricing rules

The Transfer Pricing provisions in the UAE apply to transactions or arrangements between Persons who are Related Parties or Connected Persons.

Exempt entities or entities which have elected for the small business relief, as well as standalone entities with no Related Party transactions are subject to Transfer Pricing rules and need to meet the Arm’s Length Principle in case of Controlled Transactions but are not required to prepare and keep TP Documentation.

Related Parties and Connected Persons

Related Parties

Transfer Pricing rules apply to Related Parties, which are defined under Article 35 of the Corporate Tax Law as any associated Persons, according to a specified degree of association. This association means pre-existing relationship with another Person through kinship (in case of natural persons), ownership or Control, regardless of whether that other Person is resident or not in the UAE.

The criteria for determining association between Related Parties have been categorised and detailed below:

Kinship or affiliation

The definition of kinship or affiliation covers the relationship of two or more individuals who are related up to the fourth degree of kinship or affiliation, including by way of adoption of guardianship.

In the context of the UAE [8], kinship includes common blood ties as determined by the ancestors or common ancestors of the individual, where an ancestor or common ancestor may include guardians or adoptive parents, and affiliation covers relationship by marriage, or if one natural person’s spouse is related by kinship to the other Natural Person.

Degrees of kinship or affiliation include:

The first-degree of kinship and affiliation: a Natural Person’s parents and children, as well as the parents and children of their spouse.

The second-degree of kinship and affiliation: additionally, includes a Natural Person’s grandparents, grandchildren, and siblings, as well as the grandparents, grandchildren, and siblings of their spouse.

The third-degree of kinship and affiliation: additionally, includes a Natural Person’s great-grandparents, great-grandchildren, uncles, aunts, nieces and nephews, as well as the great-grandparents, great grandchildren, uncles, aunts, nieces and nephews of their spouse.

The fourth-degree of kinship and affiliation: additionally, includes a Natural Person’s great-great-grandparents, great-great-grandchildren, grand uncle, grand aunt, grandniece, grandnephew and first cousins, as well as the great-great- grandparents, great-great-grandchildren, grand uncle, grand aunt, grandniece, grandnephew and first cousins of their spouse.

Ownership

A Natural Person and a juridical person are Related Parties by way of ownership where the individual, or one or more Related Parties of the individual, are shareholders in the juridical person, and the individual, alone or together with its Related Parties, directly or indirectly owns a 50% or greater ownership interest in the juridical person.

Two or more juridical persons are Related Parties by way of ownership if:

A juridical person, alone or together with its Related Parties, directly or indirectly owns a 50% or greater ownership interest in the other juridical person; or

Any Person, alone or together with its Related Parties, directly or indirectly owns a 50% or greater ownership interest in such two or more juridical persons.

As per Article 35(1)(b)(1) of the Corporate Tax Law, the Natural Person or one or more Related Parties of the Natural Person are shareholders in the juridical person, and the Natural Person, alone or together with its Related Parties, directly or indirectly owns a 50% (fifty percent) or greater ownership interest in the juridical person. Likewise, as per Article 35(1)(c)(1); one juridical person, alone or together with its Related Parties, directly or indirectly owns a 50% (fifty percent) or greater ownership interest in the other juridical person.

Example 2: Computation of indirect holding

Company A holds 100% ownership interest in Company B.

Company B holds 90% ownership interest in Company C.

Company C holds 80% ownership interest in Company D.

Based on Article 35(1)(c)(1), Company B is a Related Party of Company A. This is because Company A directly owns a 50% or greater ownership interest in Company B.

Two or more juridical persons can also be considered as Related Parties where one juridical person, alone or together with its Related Parties, directly or indirectly owns a 50% or greater ownership interest in the other juridical person.

In the above case, Company A indirectly has an ownership interest in Company D. The percentage of ownership interest of Company A in Company D is 100% X 90% X 80% = 72%. As the indirect ownership interest is more than 50%, Company D is a Related Party of Company A.

Control

Persons may also be considered as Related Parties through direct or indirect ‘Control’. Control is the direction and influence over one Person by another Person and can be determined in several ways including but not limited to instances where: [9]

A Person can exercise 50% or more of the voting rights of another Person;

A Person can determine the composition of 50% or more of the board of directors of another Person;

A Person can receive 50% or more of the profits of another Person; or

A Person can determine, or exercise significant influence over, the conduct of the Business and affairs of another Person.

Most of these determinants, in particular the 50% threshold, are indicators of common parent-subsidiary relationships. However, the ability of a Person to exercise ‘significant influence’ over another Person consists of the exercise of influence and direction on the conduct of a Business and may require consideration of different factors and circumstances that are specific to the scenario being tested.

The following examples illustrate how a Person can have Control by exercising significant influence over the actions of another Person, however, the underlying facts and circumstances need to be considered on a case-by-case basis when determining the existence of Control.

Example 3: Significant influence based on debt

Company X is part of an MNE Group headquartered in the UAE. It conducts Business with an independent third-party Company Z and both have developed a strong commercial relationship over the years.

Company Z decides to expand its Business and instead of approaching a bank, it approaches Company X for a loan. Company X agrees to provide a loan.

The Balance Sheet of Company Z before the loan is shown below:

| Equity and liabilities (i.e. capital) | Amount in AED million | Assets | Amount in AED million |

|---|---|---|---|

Share capital | 100 | Fixed Assets | 70 |

Liabilities | Cash and cash equivalent | 30 | |

Total capital | 100 | Total | 100 |

The Balance Sheet of Company Z after the loan is shown below:

| Equity and liabilities (i.e. capital) | Amount in AED million | Assets | Amount in AED million |

|---|---|---|---|

Share capital | 100 | Fixed Assets | 140 |

Loan from Company X | 100 | Cash and cash equivalent | 60 |

Total capital | 200 | Total assets | 200 |

In the above case, the loan from Company X constitutes 50% of the total capital of Company Z. It was also noted that after receiving this loan, Company Z registered an increase in its fixed assets and cash. A further fact-finding exercise suggests that Company X (by virtue of the loan) has started exercising significant influence over Company Z through the development of business strategy, design product portfolio and pricing, determining target customer base, and other activities, which are core to Company Z’s Business.

Based on the facts, it can be reasonably established that Company X is able to exercise significant influence and as a result both Company X and Company Z can be regarded as Related Parties.

Example 4: Establishing Control – Entitlement to Profit Share

Company A, a company resident in the UAE, has licensed a software to Company B, resident in country Y, which allows it to operate and run its day-to-day business activities in country Y.

Company A and Company B signed a royalty agreement, which entitles Company A to 50% of profits generated by Company B from the use of the software in country Y as remuneration for the use of the software.

Under Article 35(2)(c) of the Corporate Tax Law, control can be established where a Person is entitled to 50% or more profits of another Person. Thus, Company A is deemed to have Control over Company B as Company A is entitled to 50% of Company B’s profits.

Example 5: Establishing Control - Majority interest

Company X is a UAE company that is 51% owned by Company A (a UAE company) and 49% by Company Y (a foreign company).

While Company A owns a majority interest in Company X, the management of day- to-day operations, development of strategies, and formulation of the key market decisions are the functions of Company Y.

Based on the above, it can be established that Company Y has Control over Company X even though its shareholding is below 50% due to the key role in market decisions.

In this case, both Company A and Company Y would be considered Related Parties of Company X through ownership and Control, respectively.

Related Parties – additional criteria

“Related party” also means any of the following ties:

A Person and its Permanent Establishment (“PE”) or Foreign PE, [10] meaning that Transfer Pricing rules apply to transactions between a Person and their PE or Foreign PE;

Two or more Persons that are partners in the same Unincorporated Partnership; and

A Person who is the trustee, founder, settlor or beneficiary of a trust or foundation and the trust or foundation, including the trust’s or foundation’s Related Parties.

Connected Persons

Where a Person is considered to be a Connected Person of a Taxable Person, all payments or benefits provided by the Taxable Person to the Connected Person are deductible for Corporate Tax purposes only to the extent that they correspond to the Arm’s Length Price of the service or benefit provided and they are incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of the Taxable Person’s Business.

A Person is considered a Connected Person of a Taxable Person if that Person is: [11]

An individual, who directly or indirectly owns an ownership interest in the Taxable Person or Controls such Taxable Person, or a Related Party of such individual;

A director or officer of the Taxable Person, or a Related Party of the said director or officer; or

A partner in an Unincorporated Partnership, and any Related Parties of such partner.

Article 36(6) of the Corporate Tax Law specifies the categories of Taxable Persons where the deduction of payments or benefits provided to their Connected Persons is not restricted to the Arm’s Length Price. These Taxable Persons would include any of the following:

A Taxable Person whose shares are traded on a recognised stock exchange;

A Taxable Person that is subject to the regulatory oversight of a competent authority in the UAE; and

Any other Person as may be determined in a decision to be issued by the Cabinet.

International agreements for the avoidance of double taxation

The domestic legislative basis for Transfer Pricing in the UAE can be found under Articles 34 to 36 of the Corporate Tax Law. In addition, the UAE also has a well- established double taxation agreement network.

Under the terms of certain agreements entered by the UAE for the avoidance of double taxation, reference is made to “Associated Enterprises”. The OECD Model Convention defines the term and sets out the conditions that should be observed in transactions that include these “Associated Enterprises”. [12]In particular, the OECD Model Convention states that the transactions between those parties are to be conducted in a manner that is similar to those that would occur amongst independent parties in comparable circumstances.

In the event of differences between the UAE Transfer Pricing regulations and an international agreement in force in the UAE, the provisions of the international agreement will prevail.

Controlled Transactions

A “Controlled Transaction” is a transaction or arrangement between Related Parties or Connected Persons. Controlled Transactions generally include the supply or transfer of tangible goods, provision and receipt of services, funding and other financial transactions, and commercial exploitation of intangible assets such as patents, brands and know-how.

For the purposes of the UAE Transfer Pricing rules, all cross border Controlled Transactions (i.e. transactions between the Person and its Related Parties or Connected Persons that are located in different tax jurisdictions) as well as domestic Controlled Transactions (i.e. transactions between Related Parties or Connected Persons located in the UAE, including transactions undertaken between Free Zone Persons) must follow the Arm’s Length Principle.

Application of the Arm’s Length Principle

This section provides guidance on the three key steps in applying the Arm’s Length Principle for Controlled Transactions:

Step 1: Identify Related Parties, Connected Persons, relevant transactions and arrangements and perform a comparability analysis accordingly.

Step 2: Selection of the most appropriate Transfer Pricing method.

Step 3: Determination of the Arm’s Length Price.

Step 1: Identify Related Parties, Connected Persons, relevant transactions and arrangements and perform a comparability analysis accordingly

As stated in Section 3, a comparability analysis is at the heart of the application of the Arm’s Length Principle, which is based on a comparison of the conditions in a Controlled Transaction with the conditions that would have been met had the parties been independent and undertaking a comparable transaction under comparable circumstances.

A comparability analysis refers to the comparison of a Controlled Transaction with Comparable Uncontrolled Transaction(s). A Controlled Transaction and uncontrolled transactions are comparable if none of the differences between the transactions could materially affect the factor being examined in the methodology (for example price or margin), or if reasonably accurate adjustments can eliminate the material effects of any such differences.

A comparability analysis includes two key aspects:

Identifying the Related Parties, Connected Persons, commercial or financial relations between the Related Parties or Connected Persons and the conditions and economically relevant circumstances attaching to those relations in order that the Controlled Transaction is accurately delineated.

Comparing the conditions and the economically relevant circumstances of the Controlled Transaction as accurately delineated with the conditions and the economically relevant circumstances of Comparable Uncontrolled Transactions.

“Accurate delineation” refers to the recognition of the actual Controlled Transaction based on actual conduct over contractual form by analysing the functions performed, risks assumed and assets used by each party to the transaction.

This section provides guidance on identifying the commercial or financial relations between Related Parties or Connected Persons and on accurately delineating the Controlled Transaction.

Identification of the commercial and financial relations

The application of the Arm’s Length Principle depends on identifying the conditions that independent parties would have agreed to in Comparable Uncontrolled Transactions. The economically relevant characteristics and circumstances can impact the conditions of a transaction between independent parties. Therefore, it is also important to identify and consider the economically relevant characteristics of the conditions of the Controlled Transaction and the circumstances in which the Controlled Transaction takes place.

In order to understand these economically relevant characteristics, it is important to identify the commercial and financial relations between the Related Parties or Connected Persons. The typical process of identifying these relations and the related conditions and circumstances generally requires the following:

Conducting a broad-based analysis of the industry sector (for example, mining, pharmaceutical, luxury or fast-moving consumer goods) in which the Group operates and other factors affecting performance of any businesses operating in that sector, for example, competition, economic and regulatory factors.

Along with gaining an understanding of the relevant industry, it is important to have a clear overview of the Group and how the Group responds to the factors affecting performance in the industry (including its business strategies, markets, products, its supply chain, and the key functions performed, material assets used, and important risks assumed).

Analysing what each Related Party does and their commercial or financial relations as expressed in the transactions between them.

Accurately delineating the actual transaction(s) between the Related Parties or Connected Persons through an analysis of the economically relevant characteristics (i.e. comparability factors) of the transaction. This will be essential in order to choose and apply the most appropriate Transfer Pricing method, in line with Article 34(5) of the Corporate Tax Law.

The economically relevant characteristics or the comparability factors are used in two phases of a Transfer Pricing analysis.

The first phase relates to the process of accurately characterising the Controlled Transaction by performing a comparability analysis, which involves establishing its terms, functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed by the Related Parties or Connected Persons, the nature of the products transferred or services provided, and the circumstances of the Related Parties or Connected Persons. The economic relevance of the comparability factors depends on the extent to which these characteristics would be taken into account by independent parties when evaluating the terms of the same transaction were it to occur between them.

Independent parties, when evaluating the terms of a potential transaction, will compare the transaction to the other options realistically available to them, and they will only enter into the transaction if they see no alternative that offers a more attractive opportunity to meet their commercial objectives. In other words, independent parties would only enter into a transaction if it is not expected to make them worse off than their next best option. For example, one party is unlikely to accept a price offered for its product by an independent party if it knows that other potential customers are willing to pay more under similar conditions or are willing to pay the same under more beneficial conditions. In making such an assessment, it may be necessary or useful to assess the transaction in a broader context, since assessment of the options realistically available to third parties is not necessarily limited to a single transaction but may take into account a broader arrangement of economically-related transactions.

The second phase relates to the process for the comparability analysis (set out in Section 5.3) on the comparison analysis between the Controlled Transactions and uncontrolled transactions to aid in determining an Arm’s Length Price for the Controlled Transaction. During the selection of comparables, differences in economically relevant characteristics between the controlled and uncontrolled transactions need to be taken into account when establishing whether there is comparability between the situations being compared and what adjustments may be necessary to achieve comparability. These could be, for instance, unexpected situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic, Market Value fluctuations due to inflation or specificities due to a Related Party (newly established or loss-making due to specific circumstances).

After identifying the relevant commercial and financial relations, the comparability factors are analysed in detail below.

Contractual terms of the transaction

A transaction or arrangement is the expression of the commercial or financial relations between parties. Independent parties generally formalise transactions through written contracts which reflect the intention of the parties at the time the contract was concluded. Contracts typically include a description of responsibilities of the parties, its obligations and rights, assumption of identified risks, the pricing arrangements as well as terms and conditions associated with the goods or services covered.

When a Controlled Transaction has been formalised by Related Parties or Connected Persons through written contractual agreements, the agreement provides a starting point for delineating the transaction and determining how the responsibilities, risks, and anticipated outcomes arising from their interaction were intended to be divided at the time of entering into the contract.

In general, the written contracts alone may not provide all the information necessary to perform a Transfer Pricing analysis, or may not provide information regarding the relevant contractual terms in sufficient detail. In addition, the intention of the parties and key features of the intercompany arrangements may also be found outside of written contracts, for example, in emails, meeting notes, and other written correspondences between the parties. In such cases, the economically relevant characteristics in the other four categories listed above (functions performed, characteristics, economic circumstances and business strategies) will provide an important understanding of the actual conduct of the Related Parties or Connected Persons in relation to the Controlled Transaction under review.

In certain cases, no written contract exists or there may be a conflict between the written contract and actual conduct of the Related Parties or Connected Persons. In such cases, the below needs to be taken into consideration to identify the commercial and the financial relations between Related Parties or Connected Persons:

Where a transaction has been formalised by Related Parties or Connected Persons in a written contract, the starting point of any analysis should begin with the contract.

Where the conduct of the Related Parties or Connected Persons is not consistent with the terms of the written contractual agreement, further analysis of the actual conduct should be undertaken. Where there are material differences between the contractual terms and the actual conduct, the actual transaction should be determined based on the actual conduct.

Where no written contractual agreement exists, the actual transaction is determined from the evidence of actual conduct of the Related Parties or Connected Persons provided by identifying the economically relevant characteristics of the transaction, including what functions are actually performed, what assets are actually used, and what risks are actually assumed by each of the Related Parties or Connected Persons. This analysis is further described in Section 5.1.1.2.

In the event taxpayers decide to maintain written inter-company agreements, they may consider adopting a simplified approach of maintaining them based on certain materiality thresholds, criticality of transactions and arrangements, etc. such that the cost and administrative burden do not outweigh the benefits. Contractual terms that are specifically related to risks are further described under step 2 of the six-step risk framework for analysing the risks in a Controlled Transaction (see Section 5.1.1.2 below).

Functional Analysis

In transactions between two independent parties, compensation usually reflects the functions that each enterprise performs, the assets it uses, and the risks it assumes. The same principle needs to be applied to transactions between Related Parties or Connected Persons. As such, a comprehensive Functional Analysis of the Controlled Transaction is required as part of a comparability analysis to delineate the transaction and determine comparability between the Controlled Transaction and uncontrolled transactions.

A Functional Analysis seeks to identify the economically significant activities and responsibilities undertaken, assets used or contributed, and risks assumed by the Related Parties or Connected Persons in a Controlled Transaction. The Functional Analysis focuses on the functions performed by the parties and the capabilities they provide to the Controlled Transaction. These functions and capabilities will include operational activities such as procurement, marketing, sales as well as decision- making (for example, business strategy and risks).

The analysis also considers the type of assets, [13]as well as the nature of the assets used. [14]

Further, the Functional Analysis will also consider the material risks assumed by each Related Party. Usually, in an open market, the assumption of increased risk would also be compensated by an increase in the expected return. Similarly, the actual assumption and allocation of risks between two Related Parties or Connected Persons would likely affect the pricing of the transaction, so the comparable transactions would also need to reflect the increased risk.

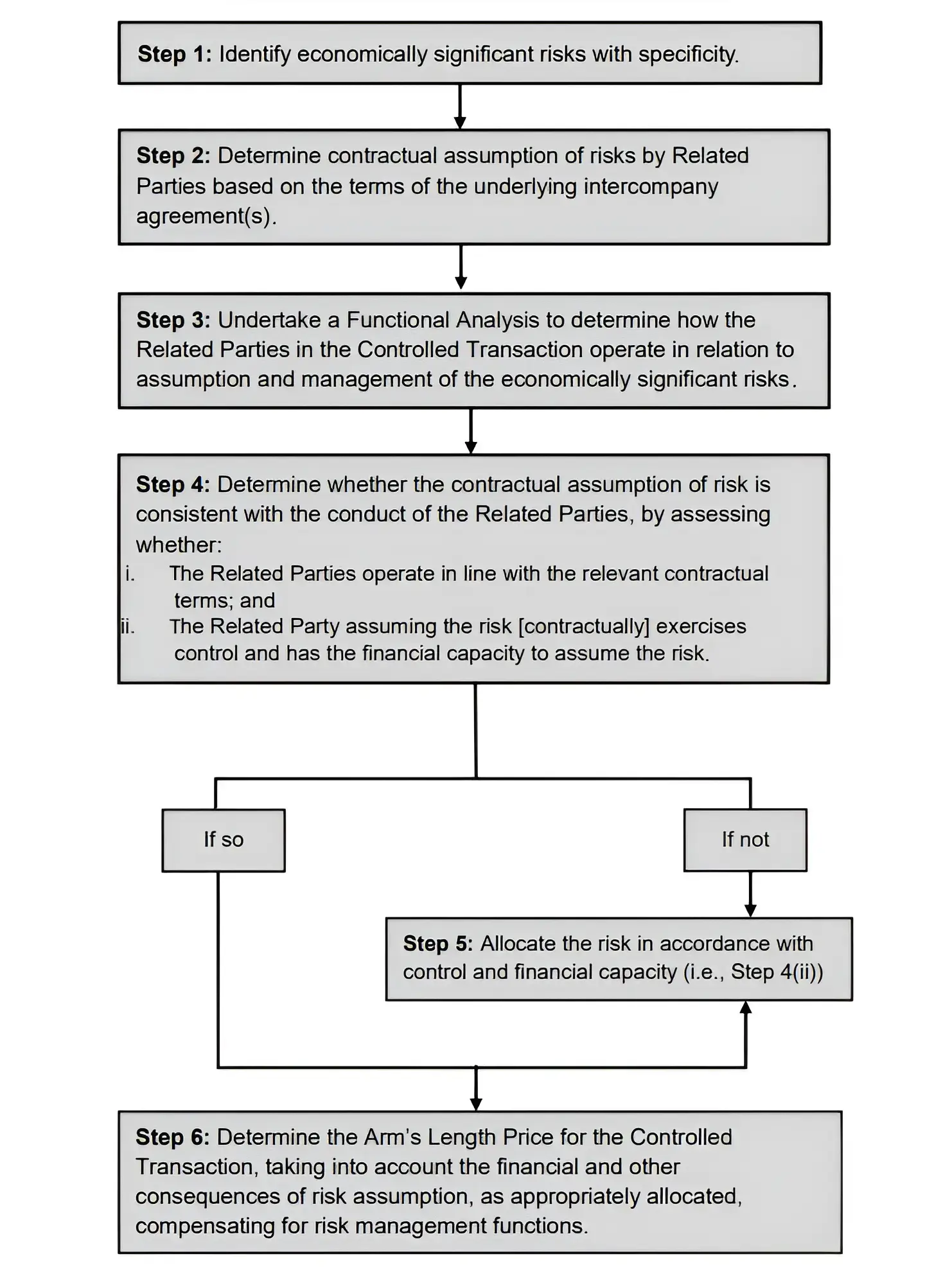

Six-step risk framework

There is a six-step process for analysing the risks in a Controlled Transaction, in order to accurately delineate the actual transaction in respect to those risks. This process is summarised as follows:

Before detailing this six-step process, the following terms need to be defined and understood:

Risk management: This refers to the function of assessing and responding to risk associated with a commercial activity. Risk management comprises three elements:

The capability to make decisions to take on, lay off, or decline a risk-bearing opportunity, together with the actual performance of that decision-making function,

The capability to make decisions on whether and how to respond to the risks associated with the opportunity, together with the actual performance of that decision-making function, and

The capability to mitigate risk, that is, the capability to take measures that affect risk outcomes, together with the actual performance of such risk mitigation.

Financial capacity to assume risk: This can be defined as having the capital or funding to take on the risk or to lay off the risk, to pay for the risk mitigation functions and to bear the consequences of the risk if it materializes. Access to funding by the party assuming the risk takes into account the available assets and the options realistically available to access additional liquidity, if needed, to cover the costs anticipated to arise should the risk materialise.

Control over risk: This involves the first two elements of risk management, that is (i) the capability to make decisions to take on, lay off, or decline a risk-bearing opportunity, together with the actual performance of that decision-making function, and (ii) the capability to make decisions on whether and how to respond to the risks associated with the opportunity, together with the actual performance of that decision-making function. Therefore, in order to exercise control over a risk, a party requires both capability and functional performance.

The six-step risk framework is further detailed below.

Step 1: Identify economically significant risks with specificity

There are many definitions of risk, but in the Transfer Pricing context it is appropriate to consider risk as the effect of uncertainty on the objectives of the business. In all of a company’s operations, in every step taken to exploit opportunities, uncertainty exists, and risk is assumed. A company is likely to direct much attention to identifying uncertainties it encounters, in evaluating whether and how business opportunities should be pursued in view of their inherent risks, and in developing appropriate risk mitigation strategies which are important to shareholders seeking their required rate of return. No profit-seeking business takes on risk associated with commercial opportunities without expecting a positive return. The downside impact of risk occurs when the anticipated favourable outcomes fail to materialise. For example, a product may fail to attract as much consumer demand as projected in practice.

Risks can be categorised in various ways, but a relevant framework in a Transfer Pricing analysis is to consider the sources of uncertainty. Examples of these risk categories include strategic, operational, financial, transactional or hazard risks.

It is important to ensure that risks are not vaguely described or undifferentiated in the contract or arrangement as this may lead to difficulties in making appropriate allocations of these risks in a Transfer Pricing analysis.

Step 2: Identify the contractual assumption of risk

The identity of the party or parties assuming risks is generally set out in written contracts between the parties to a transaction. A written contract typically sets out an intended assumption of risk by the parties, but some risks may be explicitly assumed. For example, a distributor might contractually assume accounts receivable risk, inventory risk, and credit risks associated with the distributor’s sales to unrelated customers. Other risks related to that particular type of transaction might be implicitly assumed. For example, in the case of a contract that guarantees a certain level of remuneration to one of the parties would also implicitly pass on the outcome of some risks to that other party, such as unanticipated profits or losses.

The assumption of risk has a significant effect on determining the Arm’s Length Price between Related Parties or Connected Persons, and it should not be concluded that the pricing arrangements adopted in the contractual arrangements alone determine which party assumes risk. The remaining steps of the risk framework focus on determining how the parties actually manage and control risks, which determines the assumption of risks by the parties, and impacting the selection of the most appropriate Transfer Pricing method to be applied in a particular transaction.

Step 3: Functional Analysis in relation to risk

In this step, the focus is on the functions relating to the risk undertaken by the Related Parties or Connected Persons. The analysis provides information about how the Related Parties or Connected Persons operate with respect to the assumption and management of the specific, economically significant risks, and in particular which parties perform control functions and risk mitigation functions, encounter upside or downside consequences of risk outcomes, and have the financial capacity to assume the risk in the context of the Controlled Transaction.

Step 4: Risk analysis

Carrying out steps 1-3 above involves gathering of information relating to the assumption and management of risks in the Controlled Transaction. The next step is to analyse the information collected and to determine whether the contractual assumption of risk is consistent with the actual conduct of the parties and the other facts of the case by evaluating whether:

The Related Parties or Connected Persons follow the contractual terms; and

The party assuming risk, as analysed under (i), exercises control over the risk and has the financial capacity to assume the risk.

The significance of step 4 will depend on whether the risk analysis leads to significant findings that have not been identified before. Where a party contractually assuming a risk applies that contractual assumption in its conduct, and also both exercises control over the risk and has the financial capacity to assume the risk, then the next step to consider is step 6 (disregarding step 5 on allocation of risk).

Where differences exist between contractual terms related to risk and the actual conduct of the Related Parties or Connected Persons which are economically significant and would be taken into account by third parties in pricing the transaction, the Related Parties’ or Connected Persons’ actual conduct should generally be taken as the best evidence concerning the intention of the Related Parties or Connected Persons in relation to the assumption of risk. In such a case, it is necessary to review the allocation of risk (step 5 of this risk framework).

Step 5: Allocation of risk

If it is established that the Related Parties or Connected Persons contractually assuming the risk do not exercise control over it or do not have the financial capacity to assume such risk (under step 4(ii)), then the risk should be allocated to the party exercising control and having the financial capacity to assume it. If multiple Related Parties or Connected Persons are identified as exercising control and having the financial capacity to assume the risk, then the risk should be allocated to the Related Parties or group of Related Parties exercising control over the risk in a predominant manner. When allocating the risk, the other parties performing risk control activities should be remunerated appropriately, considering the importance of the risk control activities performed.

Step 6: Pricing Controlled Transactions considering the consequences of risk allocation

Once the above steps are completed, the Controlled Transaction should then be priced in accordance with the tools and methods set out in the following sections of this Guide and considering the financial and other consequences of risk-assumption, and the remuneration for risk management. In order to be commercially reasonable, the assumption of a risk should be compensated with an appropriate return, and risk mitigation should be appropriately remunerated. Thus, a Person that both assumes and mitigates a risk will be entitled to greater anticipated remuneration than a Person that only assumes or only mitigates a risk but does not carry both.

Overall, when analysing risks, the FTA expects Persons to observe the following:

Conduct a thorough Functional Analysis to determine what risks have been assumed, what functions are performed that relate to or affect the assumption or impact of these risks and which party or parties to the transaction assume these risks. This is important even in cases where the effect of the risks assumed are not apparent in the financial statements as this does not necessarily indicate that the risks do not exist, but rather, it could mean that the risks have been effectively managed.

The pricing of the actual transaction should take into account the financial and other consequences of risk assumption, as well as the remuneration for risk management. A Person who assumes a risk is entitled to the upside benefits at the same time it incurs the downside costs.

To assume a risk for Transfer Pricing purposes, the Person needs to control and have the financial capacity to assume the risk.

Contribution to the value chain

Entities in a Group will generally conduct various activities and collaborate to deliver the relevant product or service to the Group’s customers. Some of the activities are more impactful and contribute greater value to the overall profit or success of the business, whereas other activities may be more routine or supportive in nature. As an example, activities that contribute to the intellectual property of a Group and to its value creation will typically be higher value functions than the back-office support functions. The manner in which value is added at each stage in creating a product or service is known as the value chain.

Different industries and business models will have different value chains and key value drivers. As part of the Functional Analysis, it is, therefore, important to understand the relative value and contributions of each Related Party to the overall value chain of a business and the relevant product or service.

The findings of the Functional Analysis define the roles of each Related Party and assign a functional characterisation, ranging from entrepreneurial to low or no-risk entities based on the functions performed, assets employed, and risks assumed by each party.

Practical guidance for undertaking a Functional Analysis

Understanding the functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed by the parties to the transaction through a Functional Analysis assists in understanding the contribution of these parties to the value chain and, therefore, in arriving at the appropriate compensation for their activities (see Section 5.3 for further details).

As a practical guide when conducting a Functional Analysis, a functional organisation chart could be prepared for each of the parties involved in the Controlled Transaction. This functional organisation chart should identify the relevant departments and personnel within the organisation together with the functions that they perform. For the personnel, stating the title is not sufficient; information is required on the functions performed (for example, via a job description) and the actual conduct of such personnel, and on how the compensation is structured etc.

A Functional Analysis may begin by undertaking an interview with the relevant departments and personnel, and questionnaires are generally used as an indicative guide to the interviews.

Example 6: Samples of Functional Questionnaires

Table 1 below shows an example of a sample list of questions that may be considered relevant for performing a Functional Analysis for a manufacturing entity. This list is not intended to be exhaustive and should be amended to cover the relevant aspects of the specific industry, characteristics of the Business of the Person, and the nature of the Controlled Transaction being analysed. Further, these types of questions are typically used as an indicative guide to undertaking Functional Analysis interviews, and are generally not followed verbatim during such interviews.

Table 1: Sample Functional Questionnaire - Functions (Manufacturer)

| Functions | Questions |

|---|---|

Planning |

|

Manufacturing |

|

Procurement |

|

Sales |

|

Shipping |

|

Quality Control |

|

Warehousing |

|

In addition to the above functions, businesses may also employ tangible and intangible assets in their activities.

Continuing with the above example, a manufacturing entity may use the following assets that should be evaluated in a Functional Analysis:

Table 2: Sample Functional Questionnaire – Assets (Manufacturer)

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

Tangible (Routine and non-routine) |

|

Intangible (Routine and non-routine) |

|

Finally, a manufacturing entity may also assume the following risks which would need to be considered as part of the 6-step risk framework:

Table 3: Sample Functional Questionnaire - Risks (Manufacturer)

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

Credit Risk | Credit risk can represent the financial loss that would be recognised at the reporting date if counter parties failed completely to meet their contractual payment obligations, for example, bad debt or overdue receivables from the manufacturer’s customers. |

Foreign Exchange Risk | Foreign exchange risk occurs when there is a mismatch in the currency of the Controlled Transaction, reporting currency, or currency of significant revenues or expenses, for example, exchange rate movements resulting in material increase in cost of imported raw materials obtained in the foreign currency. |

Market Risk | Market risk relates to market factors that may impact the profits of the business. Market risk may arise due to increased competition and relative pricing pressures of the manufactured product, change in demand patterns and needs of customers for the product manufactured, and the inability to develop/penetrate a market. |

Inventory Risk | Inventory risk relates to the inventory held by a company that becomes obsolete or physically damaged before the manufactured product is sold. |

Product Liability Risk | Product liability risk is associated with product failures including non-performance to generally accepted or regulatory standards. This could result in product recalls and possible injuries to end-users. |

Below is an example of a high-level Functional Analysis of a manufacturer whose products are distributed by a Related Party. This example is illustrative and simplified (as compared to a full Functional Analysis) in order to highlight the key areas that are important in undertaking such an analysis.

Example 7: Functional Analysis of manufacturing entity Company A

Overview

The Functional Analysis example below focuses on Company A which is a manufacturer of microchips based in country X. Company A operates through a network of subsidiaries in multiple countries, engaged in the global distribution of microchips produced by Company A in country X.

Functions performed

Research and Development

Company A has an R&D department comprised of 50 full time employees, headed by a technical director who reports directly to Company A’s board of directors based in country X. The department operates through teams engaged in technical functions related to the development, enhancement and maintenance of the hardware and software aspects of the microchips produced by Company A.

Sourcing

Company A has a procurement department staffed with 50 full time employees who have extensive experience in sourcing raw materials in the technology development industry. Working closely with the finance and legal department at Company A, this team undertakes end-to-end vendor due diligence and onboarding, including functions related to vendor identification, reviews, negotiations, selection and relationship management. In addition, the department manages purchase planning and scheduling, inbound logistics and preliminary quality and specification control in relation to the sourced raw materials.

Manufacturing

Company A owns and operates special purpose manufacturing assets and facilities for production of its branded microchips in country X. The facility is operated by a team of 3 engineers, 7 technicians and 40 assembly staff, led by the company’s Director of Engineering. The facility incorporates patented production processes based on in-house designed components, which gives Company A its competitive advantage and differentiates its products in the market. Capacity utilisation and production planning is managed by Company A’s Director of Engineering in alignment with the company’s board of directors.

Inventory management

Company A owns and operates a warehouse for storage of raw materials and finished products in country X. Company A has developed inventory management policies implemented at the level of country X, as well as in the overseas territories where the distribution subsidiaries are located. The policy features standard operating procedures for stock management, re-orders, planning and risk management. Company A monitors performance of the distributors in terms of compliance with the inventory management policies. Three employees of Company A are responsible for inventory management.

Quality control

Company A’s preliminary controls are undertaken by its procurement team at the point of raw material sourcing. Subsequent controls are integrated into the manufacturing process, with sample tests and technical evaluations of semi-finished and finished products conducted before they are transferred to the packaging lines. Company A’s quality control framework also includes reporting standards and procedures which must be completed before batches are shipped out to the distributors. 5 employees of Company A perform the quality control function.

Logistics

Company A enters into long term multi-territory contracts to work with third party transportation and logistics services providers who provide outbound logistics support in transporting the finished goods to the distributors. The selection of other in-country logistics service providers subcontracted by the distributors is subject to review and approval of Company A. Company A also bears insurance costs related to global freight risk. 10 employees of Company A perform the logistics function.

Marketing

Company A’s marketing team develops the group marketing strategy and identifies and targets new customers through tailored promotions for each country. Company A has three full time employees in the marketing team. The distributors provide on- ground market intelligence which may inform Company A’s product customisations for their respective markets. Local campaigns are run on marketing materials centrally prepared in line with the global brand guidelines set and periodically reviewed by Company A.

Sales and distribution

All of Company A’s products are sold through its network of Related Party and third- party distributors in both wholesale and retail channels. Sales are store-led and are also made through third party online marketplaces. 30 individuals employed by Company A are responsible for this function.

Sales projections and targets

Company A develops the global sales strategy, budget and targets, taking into account local market inputs from the distributors who provide information on market developments in their respective territories. Company A may revise the targets during a given period at its discretion. 10 individuals employed by Company A are responsible for this function.

Pricing

Company A is responsible for determining the pricing policy and profit margins at which its products are sold. Pricing is determined based on various market forces, costs incurred and global competitive landscape. Company A also sets the global discount policies and sales promotional offers whereby any local market deviations are subject to approval of the Commercial Director who is employed by Company A. 3 individuals employed by Company A are responsible for this function.

Working capital financing and management

Company A’s finance department manages global cash flow and liquidity positions, determines sources and the nature of external financing. Company A also determines the receivables and collection policies implemented globally, monitors movements in distributors’ inventory levels, holding costs and outstanding payables from a liquidity management perspective. 20 individuals employed by Company A are responsible for this function.

Customer relationships

Company A defines the guidelines and policies for key account management globally. Global priority accounts are directly maintained at the level of Company A, with local coordination and assistance provided by the distributors. Company A maintains direct lines of communication with its key accounts. The distributors manage routine customer enquiries and support related issues in line with the guidelines set by Company A. Critical customer concerns are directed upwards to Company A on case-by-case basis. Company A maintains a database of global customer lists.

After sales services

The distributors provide after-sales support services, mostly with regards to registering customer complaints / enquiries, provide support to customers with regard to defective product claims and product recalls. Significant complaints / claims are reported upwards. Company A bears the costs associated with customer claims and returns.

Assets employed

Tangible assets

Company A owns significant manufacturing and storage facilities including its factories, equipment and warehouses. The distributors operate through leasehold properties, utilising routine tangible assets such as office fixtures and related equipment.

Intangible assets

All patents and branding elements used by the group are developed by Company A and registered under the legal name of Company A. The distributors do not own any significant intangible assets.

Risks assumed

Market risk

This relates to the risks of losses arising from movements in the market variables like prices, volatility, increased competition in the marketplace, adverse demand conditions or the inability to develop markets or position products to service targeted customers.

Inventory risk

Inventory risk relates to the losses associated with carrying raw material or finished product inventory. Losses include obsolescence, shrinkage, destruction, or market collapse such that products are only saleable at prices that produce a loss.

R&D risk

This is the risk that the efforts devoted to the innovation, and improvement of its products and processes.

Forex risk

This is the risk of expected and unexpected gains or losses on foreign currency fluctuations.

Capacity utilisation risk

This risk is associated with inefficiency in utilising the production capacity which adversely affects the manufacturing process.

Product liability risk

Product liability risk refers to a supplier’s exposure to losses due to failure of its products to perform as represented to customers.

Functional characterisation