TRIANGULAR TAXATION: WHEN THE INTERNATIONAL TAX SYSTEM STOPS BEING LINEAR

Excerpt

International tax treaties are designed on a bilateral basis and work well for two-country situations, but they struggle when income is connected to three jurisdictions. In these triangular cases, different countries may tax the same income under separate treaties and domestic laws, even though n...

Introduction

International tax treaties are often described as the plumbing of the global economy. For over a century, they have operated quietly to prevent income from being taxed twice as it moves across borders, allowing capital and people to move with relative certainty. Most of the time this bilateral system works well, but it assumes a simple world with one source country for the income and one residence country for the taxpayer. Complications arise when a third country enters the picture. When income is connected to three jurisdictions instead of two, the treaty framework, built on thousands of bilateral agreements, starts to creak. These situations are known as triangular cases, and it is in these three-country scenarios that the risk of unrelieved double taxation often lurks in plain sight.

Structural challenges of triangular taxation

The international tax regime is not a single unified code but a patchwork of bilateral treaties, each negotiated independently between two states.

Each treaty addresses a narrow question: How to allocate taxing rights between Country A and Country B?

What treaties do not directly address is a broader question: What happens if Country C also has a legitimate claim on the same income?

Triangular tax cases are therefore not aberrations but a structural blind spot stemming from the bilateral design of tax treaties. No individual treaty is "wrong" in these cases, yet the combined application of multiple treaties (and domestic laws) can produce over-taxation, under-taxation, or sheer uncertainty in outcomes.

The OECD Model Tax Convention ("OECD MTC") and its commentary have long acknowledged this structural difficulty. In fact, the Commentary notes that situations involving more than two states "raise many problems" and that the standard bilateral treaty provisions offer no automatic solution. There is no general provision in the OECD MTC requiring any country to grant relief for tax imposed by a third state under a different treaty. Instead, resolving a triangular case is essentially left to countries to work out between themselves, either by inserting special provisions in their treaties or through case-by-case Mutual Agreement Procedures ("MAP") (OECD MTC 2017, Commentary on Article 23, para. 10).

In short, the bilateral nature of treaties means that triangular scenarios create gaps: each treaty sees only its two contracting states, and tax imposed by a third state may fall outside the intended co-ordination.

Triangular Case 1: Corporate income earned through a third-country permanent establishment

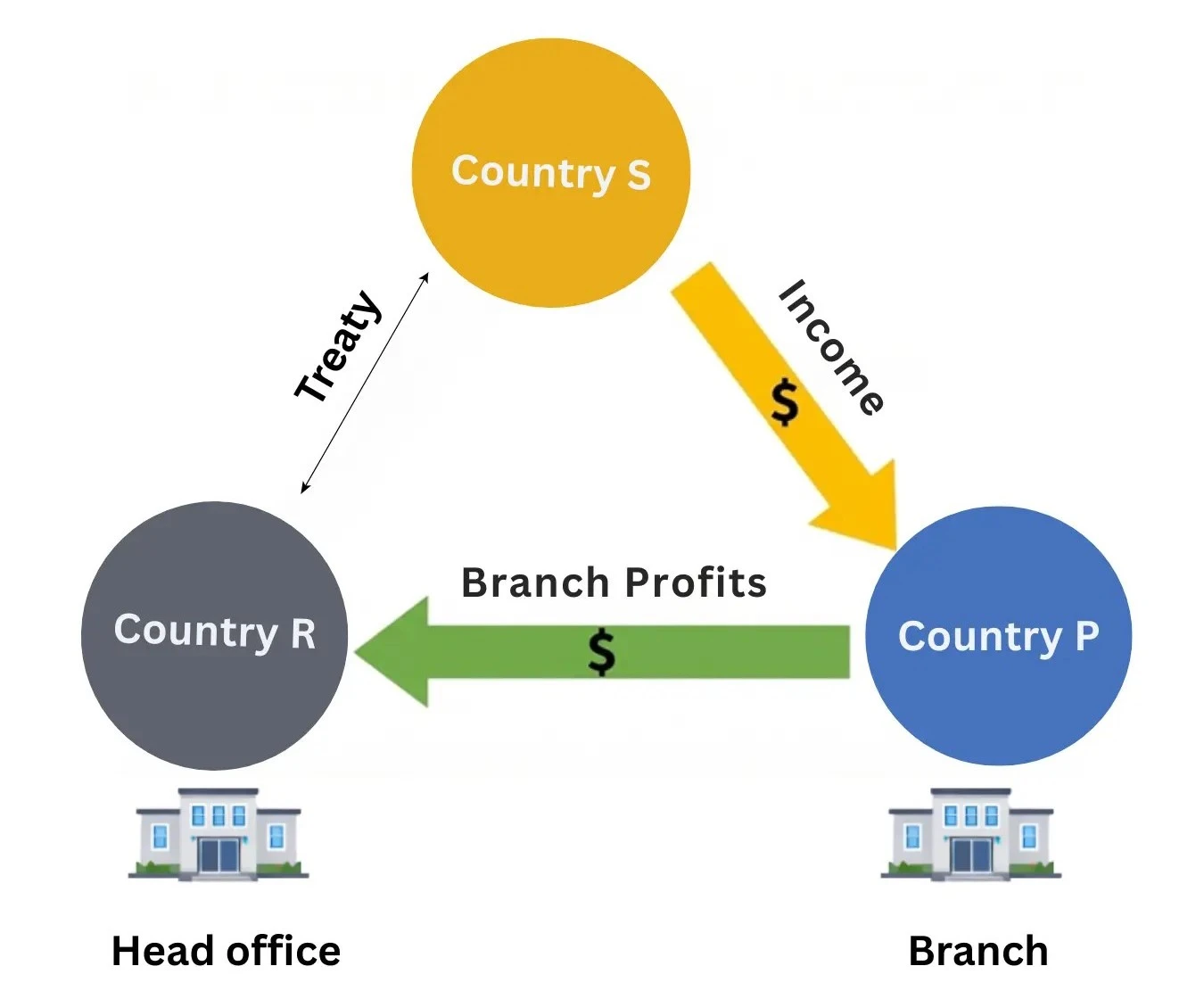

One of the most common triangular cases involves a corporate business with operations in three countries. Suppose:

- A company is a tax resident of Country R (Residence),

- It operates a branch (permanent establishment, or "PE") in Country P (PE country); and

- Such branch earns income from Country S (Source).

Under basic treaty principles, profits attributable to the branch (the PE) are taxable in Country P (the host country of the PE) and Country R is expected to relieve double taxation on those branch profits under the R-P tax treaty. At first glance this seems straightforward, and indeed most R-P treaties (following the OECD Model's Article 7 and Article 23) provide that Country R will either exempt the branch profits or credit the tax paid in Country P.

However, complications arise at the point of actual payment from Country S to the branch in Country P. From Country S's perspective, the payment is being made to an enterprise of Country R (since the branch is not a separate legal person). Consequently, Country S will typically apply the tax treaty between S and R - treating the company as a resident of Country R and ignoring the branch's presence in Country P for withholding purposes. This approach is consistent with the design of tax treaties: a treaty applies only to persons who are residents of one or both contracting states (OECD MTC 2017, Article 1). A branch is not itself a "person" or a "resident" under treaty definitions, but merely an extension of the company in Country R (OECD MTC 2017, Commentary on Article 4, para. 8).

In other words, the PE in Country P cannot independently claim treaty benefits because it is not a resident of Country P in its own right, being liable to tax there only on a source basis and not on worldwide income. Country S, therefore, withholds tax according to the S-R treaty (assuming one exists), which generally permits source country taxation (often at a reduced rate for dividends, interest, royalties, etc., or under Article 21 for other income).

Meanwhile, Country P taxes the income because it is attributable to a PE located in P. The branch profits are included in P's tax base under domestic law and typically also under the P-R treaty (Article 7 business profits).

Now we have two levels of source taxation on the same income: Country S has levied withholding tax, and Country P taxes the net branch profits.

Which treaty comes into play to relieve this double taxation? Country R, as the company's residence state, is the one looking at income that has already been taxed in two other states. Under the R-P treaty, Country R is obliged to relieve double taxation on the branch profits (e.g. by exempting them or crediting P's tax).

However, the tax paid in Country S does not neatly fit into this bilateral framework: the R-P treaty does not mention Country S, and the S-R treaty does not mention Country P. This raises a series of questions that highlight the inherent ambiguities:

Which treaty governs the source tax withheld by Country S?

In practice, Country S is applying the S-R treaty to justify its withholding. From Country S's perspective the recipient is a resident of Country R, so S sees no role for the P-S treaty (even if one exists) because the payment is not made to a Country P resident. The branch in Country P is "invisible" to Country S for treaty purposes. This means the withholding tax by Country S is imposed under the allowances of the S-R treaty (or under Country S domestic law if no treaty benefit is claimed).

How does Country R view the nature of this income?

Country R taxes its resident company on a worldwide basis, so it includes the income arising in Country S (via the branch) in the company's taxable income. Economically, though, Country R might view it as part of the branch's profits that were earned through the PE in Country P. Country R must then decide which tax treaty (and which article) applies when granting relief.

One possibility is to treat the income as covered by the R-P treaty (as branch profits), in which case Country R might aim to relieve Country P's tax (exempting the branch profits or crediting P's tax), while considering S's withholding as outside the scope of that treaty.

Alternatively, Country R could consider the Country S source income under the R-S treaty, crediting the tax paid to S, but then how would it account for Country P's taxation?

In short, Country R faces a treaty overlap: two different bilateral treaties (R-P and R-S) potentially apply to different legs of the transaction, and neither treaty alone covers the full triangular situation.

What is the status of the withholding tax paid in Country S?

This is the critical fault line. Country R needs to determine whether the tax paid in Country S will be credited or exempted, and under which treaty's obligation. Under the R-P treaty, Country R's obligation is clear regarding Country P's tax on the PE profits, but that treaty does not obligate R to relieve tax paid to a third country (S). Under the R-S treaty, Country R would typically grant a credit for Country S's withholding tax if the income is considered directly as income of a resident of Country R (which nominally it is). However, if Country R is simultaneously exempting that income under the R-P treaty (because it regards it as branch profits taxable in P), there is a potential conflict or "dual relief" problem:

Country R might end up having to both exempt the income (due to the R-P treaty) and credit the Country S tax (due to the R-S treaty) in order to fulfill its obligations under both treaties. This kind of dual relief is not intended by treaties and could even result in non-taxation, so countries often prevent or resolve such overlaps through specific provisions or administrative practices.

The OECD Commentary notes that a residence country in a triangular case may not be able to fully relieve double taxation when income is taxed in both the PE state and the source state, and that if treaties would demand "dual" methods (exemption and credit) for the same income, it would be problematic (OECD MTC 2017, Commentary on Article 23). In practice, Country R must interpret its treaty obligations in a coherent way, often by crediting the source tax from Country S against its own tax (under domestic law or the R-S treaty) while exempting or crediting Country P's tax to the extent necessary, taking into account any domestic rules on per-country or overall credit limitations.

Is Country R obliged to grant relief for Country S’s tax, and if so, who gives that relief?

This question has different answers depending on the treaties and domestic laws involved. The OECD Model's standard provisions (Article 23A for exemption or 23B for credit) require Country R to relieve double taxation for income that Country P is entitled to tax under the R-P treaty. They do not explicitly require relief for tax that Country S charges, because Country S is not a party to the R-P treaty. As a result, if Country R were to strictly follow the R-P treaty, it might exempt the branch income taxed in P but provide no credit for Country S's withholding, since that tax is outside the R-P treaty's scope. The OECD Commentary explicitly notes that the Convention has "no provision" compelling the Country P to provide relief for taxes paid in Country S, and by extension, the residence country's treaty with the PE country does not compel relief for third-state tax either. Whether Country R relieves Country S's tax then often depends on Country R's domestic foreign tax credit system. Some countries' domestic laws allow credits for any foreign income taxes paid, even outside treaty situations, in which case Country R might unilaterally credit the tax paid to Country S. Other countries restrict credits to treaty-covered taxes or to specific countries, which could mean Country S's tax is not creditable in Country R absent a treaty obligation. This is why in many triangular cases, the residence Country R might end up giving relief for Country S's tax as a matter of practice or unilateral policy rather than strict treaty obligation.

Does Country P have any obligation to relieve Country S’s tax on the branch income?

Country P, the PE host, is taxing the branch's profits as its source income. Country P typically would not give a credit for Country S's withholding tax because, from Country P's perspective, the income did not arise outside Country P's own jurisdiction (it arose in Country P's branch operations, albeit paid from Country S). However, one treaty provision potentially comes into play: the non-discrimination clause.

Article 24(3) of the OECD MTC provides that a contracting state (Country P) shall not tax a PE of an enterprise of the other state (Country R) "less favorably" than it taxes its own enterprises in similar circumstances. The OECD Commentary on Article 24 suggests that if P's domestic law grants foreign tax credits to its own residents for taxes paid to third countries, the same credit should be extended to PEs of foreign enterprises in Country P. In other words, Country P cannot deny a credit to the Country R company's branch for Country S's tax if Country P would have allowed that credit to an enterprise of Country P carrying on the same activities and earning income from Country S (this would be a discrimination based on nationality of the enterprise). However, if Country P's domestic law does not provide any credit to its residents for third-country taxes, Article 24 does not force Country P to create a new relief.

Is relief for the overlapping taxes automatic or does it require competent authority intervention?

Even where a country's domestic law or treaties in principle allow relief, practical issues can arise. For example, if Country R uses the credit method, it might impose per-country limits that cap the credit for taxes paid to any one foreign state. A triangle can break those assumptions: Country R might have separate limits for Country P and Country S, potentially leaving some Country S tax uncaptured if the income is classified as sourced from Country P. Alternatively, Country R might only discover the issue upon audit or taxpayer request, requiring a Mutual Agreement Procedure ("MAP") between Country R and Country P (or Country R and Country S) to resolve double taxation. In some cases, tax administrations only grant relief for complex triangular situations after the taxpayer initiates a MAP under Article 25, especially if the interaction of treaties is unclear. The process can be discretionary and slow. Thus, two companies with identical operations but headquartered in different countries could face very different outcomes: one country's system may automatically credit both P and S taxes, while another country may provide no relief for S's tax unless negotiated after the fact.

For a tax advisor examining a corporate structure, a clear red flag is when income is being taxed in a country that the relevant treaty does not "see." In this PE example, Country S is that unseen third party from the perspective of the R-P treaty. This misalignment is where unrelieved double taxation often originates. If part of the tax is outside the coordinated treaty scope, the foreign tax credit mechanism can break down, leaving a portion of tax cost "stuck" with no relief. Practitioners should be alert to any such misalignment and consider planning or treaty provisions (such as specialized triangular relief clauses or MAP) to address it.

Triangular Case 2: An individual with two residences and third-country income

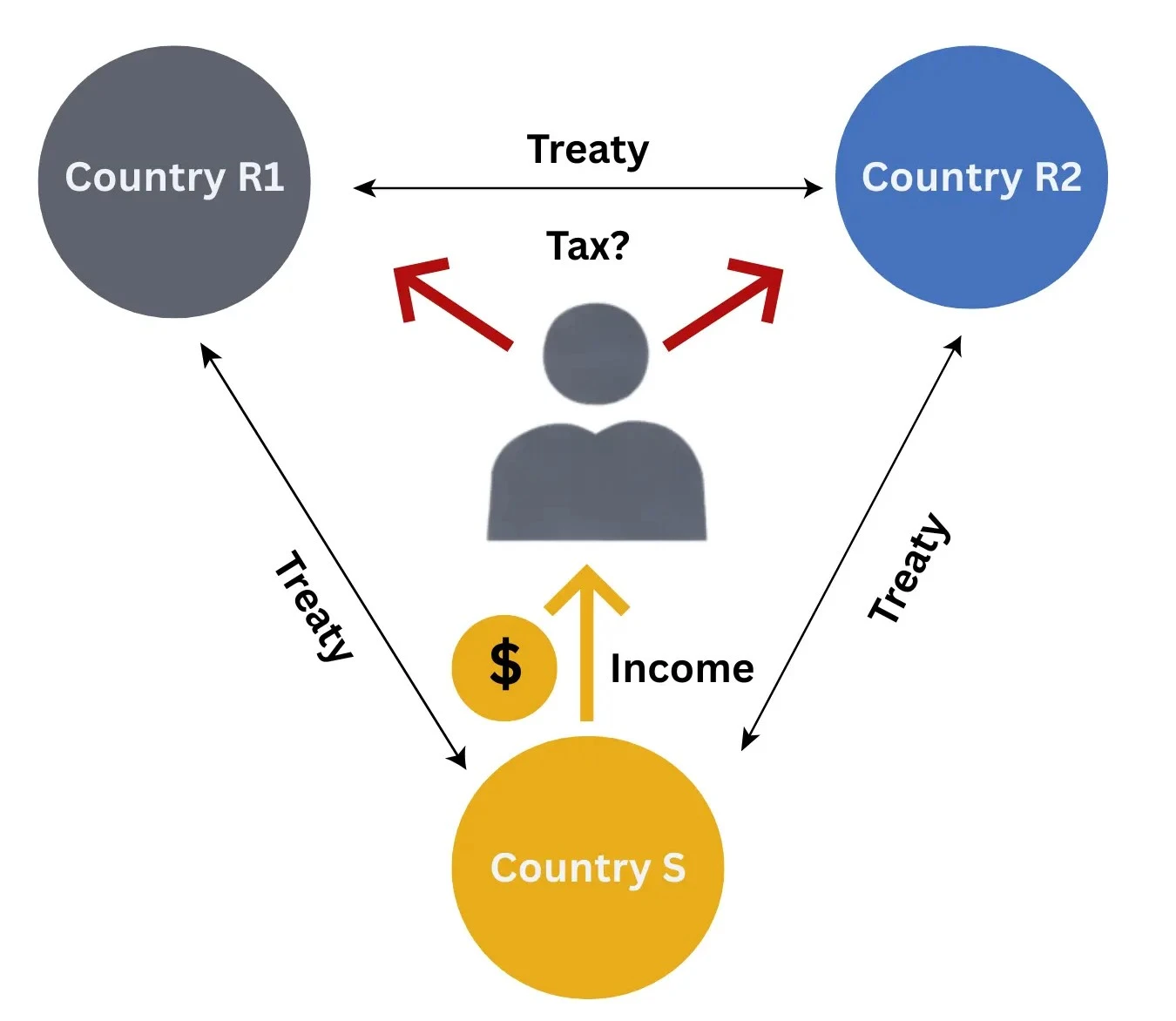

Triangular issues are not limited to companies. They increasingly arise for globally mobile individuals. Consider an individual who has connections to three countries: Country R1 treats the individual as a tax resident under its domestic law. Country R2 also treats the same individual as a resident under its law. Country S is the country where the individual's income arises (and where source-based tax, such as withholding, is imposed).

A classic tax treaty situation of dual residence (R1 and R2) is normally resolved by a tie-breaker test in the treaty between R1 and R2 (OECD MTC Article 4(2)). For individuals, this tie-breaker looks at factors like permanent home, center of vital interests, habitual abode, and nationality to assign a single treaty residence. Assume R1 and R2 do have a tax treaty and the tie-breaker deems the person to be resident only of R1 for purposes of that treaty. This solves which of R1 or R2 has the treaty "claim" to be the residence in their bilateral relationship. But now introduce Country S, the source of the income, and ask: which treaty does Country S apply to this individual's income? From Country S's perspective, the individual might present a residency certificate from either Country R1 or Country R2 (potentially from both). In principle, the individual could claim treaty benefits through either of the two residence countries' treaties with Country S.

For example, if the person shows residence in Country R1, Country S will apply the S-R1 treaty and impose source tax accordingly (often reducing its tax under treaty limits). Country S is not concerned that Country R2 also considers the person a resident. Country S looks only at the single treaty being invoked for relief at source. In most cases, an individual will choose to invoke the treaty of the country that provides the best source-tax reduction or where they can obtain a residency certificate. Thus, Country S might never even become aware of the dual-residence situation. It will grant, say, a reduced withholding rate under the S-R1 treaty and call it a day.

The real complexity lies with the two residence countries, Country R1 and Country R2, and how they tax and give relief. By domestic law, each of those countries sees the individual as a resident and thus taxes the individual's worldwide income (including the income from Country S). Now, if the R1-R2 treaty tie-breaker settled that the person is resident only of Country R1, one might expect Country R2 to yield. Indeed, the OECD's position is that once a dual-resident individual is treated as resident of Country R1 by the tie-breaker, the other state Country R2 should treat that individual as a non-resident for treaty purposes with respect to third countries (because Country R2 is now only taxing that person on income from sources in R2 itself).

The Commentary explains that under the second sentence of Article 4(1), a person who is liable to tax in a state only by reason of income from sources in that state is not a "resident" for purposes of the treaty. In our example, after the tie-breaker, Country R2 should only tax the individual on Country R2-source income and not as a full resident, effectively meaning Country R2 would not claim this person as a resident for any treaty with Country S (OECD MTC 2017, Commentary on Article 4, para. 8.2). This approach prevents the individual from having dual treaty resident status and claiming double benefits.

However, this interpretation is not universally enforced and has been described as controversial. It relies on the losing residence Country R2 applying the treaty tie-breaker outcome in a far-reaching way, including how it interacts with third states. Not all countries may interpret their laws or treaties to automatically withdraw treaty resident status in third-country relations.

What if Country R1 and Country R2 do not have a treaty or the tie-breaker is inconclusive? For instance, imagine Country R1 and Country R2 have no tax treaty - then there is no tie-breaker at all, and the individual is fully liable to both on worldwide income. Or perhaps the treaty exists but the tie-breaker is based on mutual agreement (as is now the case for dual-resident companies under the post-2017 OECD MTC, and potentially for individuals if the facts are not clear). In such situations, the individual might end up being treated as a resident by both countries simultaneously with no definitive tie-break. Tax treaties are designed to relieve double taxation between a source and a residence country; they do not contain a rule to resolve conflicts when two countries both claim to be the residence. As the OECD Commentary points out, treaties allocate income taxing rights primarily between one residence and one source, and they do not obligate either of two residence countries to cede or relieve tax paid to the other. Thus, if Country R1 and Country R2 both insist on taxing the individual as a resident, neither is obliged under any treaty to give credit for taxes paid to the other (since each sees the other as not a source state but another residence). This can result in genuine double taxation of the same income by two residence states. Even if Country S grants a treaty reduction at source, the individual's income is still being taxed in full by Country R1 and Country R2 on the back end, with no relief for one another's taxes.

This leads to practical questions in advising a dual-resident individual:

Which country will ultimately be considered the residence for treaty purposes?

If a tie-breaker rule clearly assigns residence to Country R1, then in theory the individual should claim treaty benefits as a resident of Country R1 (and Country R2 should refrain from treaty claims). The individual's home and personal connections will be crucial in applying the tie-breaker tests (OECD MTC 2017, Commentary on Article 4, paras. 15-20, for example, discuss how to determine "center of vital interests"). If there is no tie-breaker, the individual might try to arrange affairs to not be a factual resident of one country or otherwise reduce exposure, but legally both claims stand until resolved.

Will both residence countries provide relief for source-country tax (and for each other’s tax)?

Suppose Country S withholds, say, 15% tax under a treaty. Now both Country R1 and Country R2 tax the income at their rates (which could be much higher than 15%). Ideally, only one of Country R1 or Country R2 should be the true residence (post tie-breaker) and thus only that country needs to provide a foreign tax credit for Country S's withholding. The other country (if it concedes residence) would treat the person as non-resident and only tax its local income. Problems arise if both countries still tax globally: will each give a credit for Country S's tax? Perhaps only one will (the one the taxpayer chooses to credit first), or each might credit only up to its share of the income tax. Worse, if Country R1 and Country R2 also tax the income and neither relieves the other's tax, the individual faces triple taxation (R1 + R2 + S) with only Country S's portion possibly credited. In practice, many dual-resident situations are resolved through MAP if a treaty exists (the two tax authorities can negotiate to assign a single residence and eliminate double taxation). But MAP can be time-consuming and is not guaranteed to succeed. The individual may need to pay both taxes and then seek refunds via MAP or domestic claims. If no treaty exists between Country R1 and Country R2, the only hope might be unilateral relief: for example, one country might have a rule to credit foreign taxes paid by its residents even if the foreign country considers the person a resident too. Such cases are rare and usually require diplomatic or discretionary solutions.

Diagnosing a Triangular Tax Risk

Regardless of whether the taxpayer is a corporation or an individual, triangular cases can be analyzed through a common diagnostic framework. A tax professional may consider seeking answers to these key questions when three jurisdictions are involved:

- Which countries have taxing rights, and on what basis?

Identify all states that might tax the income either by residence, by source, or by attribution through a PE or fixed base. In our examples, Country R, Country P, and Country S all asserted some taxing right (Country R and Country R2 by residence, Country P and Country S by source). Understanding each country's claim (and whether it's primary or secondary) is the first step. - Which tax treaty is being invoked (or ignored) at each stage?

In a triangular scenario, different countries may be applying different bilateral treaties to the same income flow. For instance, Country S applies its treaty with Country R, while Country R looks to its treaty with Country P, etc. It is crucial to map out which treaty each jurisdiction is using as the basis for its taxation or relief, and whether any country is effectively taxing outside of a treaty framework. If a country is taxing income that another country's treaty position does not "see" (for example, Country S's tax from the perspective of the R-P treaty, or Country R2's tax from the perspective of R1-S), that disconnect is where double taxation is likely to emerge. - Is any portion of the income being taxed by a country outside the relevant treaty context?

This is essentially asking if there is an orphan tax: a tax imposed by a jurisdiction that isn't accounted for in the relief provisions of the treaty being relied upon by the residence country. In the PE case, Country S's withholding was outside the R-P treaty's scope, and in the dual-resident case, each residence country's tax was outside the other's treaty scope. These are the pressure points where unrelieved double taxation usually originates. - Who is expected to grant relief, and are they obligated (and able) to do so?

Determine which country is supposed to eliminate the double tax under normal treaty principles. Is it the primary residence country's responsibility to credit or exempt the foreign taxes? Does the PE host country need to give a credit because of non-discrimination? Or is relief only available if the competent authorities work out a solution? One must check the exact treaty provisions: for example, Article 23 of the OECD Model makes the residence country responsible for relief of source taxes, but it does not explicitly cover relief for third-country source tax. Similarly, Article 24(3) might put an obligation on the PE country to give relief comparable to that given to its own residents, but only if its domestic system provided such relief in the first place. If the identified "relief provider" has no clear legal obligation or mechanism to relieve the tax, then the double taxation will persist unless a MAP or unilateral relief steps in. The practitioner should verify if relief is automatic under domestic law or treaty, or if it will require negotiations (and then consider the likelihood of success of those negotiations).

By systematically asking and answering these questions, one can often spot a triangular problem before it crystallizes. If any of the above questions has an unclear answer or reveals a mismatch, the triangular risk is real and significant. Early diagnosis allows for restructuring transactions or seeking advance clearance (for example, an Advance Pricing Agreement or a multilateral MAP) to avoid getting caught in a three-way tax trap.

Why triangular tax cases are becoming more common?

Triangular tax scenarios are no longer exotic corner cases. They have become more frequent in today's globalized economy, arising naturally from modern business models and lifestyles. Multinational enterprises often have cross-border operating structures where, for instance, a regional hub in one country manages investments or intangibles that generate income from various other countries. Businesses increasingly centralize functions like treasury or Intellectual Property ("IP") ownership in a third jurisdiction separate from both the ultimate parent company's country and the source markets, which is a fertile ground for triangular issues. Furthermore, key decision-makers and management may operate remotely from yet another country (especially with the rise of remote work and digital business), creating situations analogous to a PE in a management location separate from both the company's home and the market country. At the same time, globally mobile individuals are more common, and they can easily end up dual resident or earning income in third countries as in the example above. All these trends mean that scenarios involving three (or more) tax jurisdictions are arising with greater frequency in both corporate and individual contexts.

What makes triangular cases particularly challenging is that every tax position taken by each country might be entirely reasonable and within the law when viewed in isolation. Each tax authority is simply applying its domestic law and bilateral treaties: Country S taxes at source, Country P taxes the local branch, Country R1 and Country R2 tax their residents. Yet the combined outcome can be punitive, often in ways that are not immediately obvious. The risk is that double (or even triple) taxation is only detected when the tax returns are filed or when a tax credit is denied, by which time the mismatch has already created a costly problem. Conversely, there is also potential for double non-taxation in certain triangular setups (for example, if neither residence country taxes certain income, each thinking the other will, or if dual relief inadvertently wipes out tax). This is why tax planners and administrators are paying closer attention to triangular cases now, especially post-BEPS when tackling both double non-taxation and unintended double taxation are on the agenda.

Until the international tax system moves beyond its bilateral foundation, triangular cases will remain an inherent stress point. Multilateral instruments (such as the BEPS Multilateral Instrument, which includes a provision addressing certain PE triangular treaty abuse situations) and bespoke treaty clauses (like those in some U.S. treaties that deal with tri-state situations) offer partial fixes, but they do not eliminate all triangular problems. The role of the tax professional, therefore, is not only to ensure compliance with each applicable law, but to anticipate and plan around triangular pitfalls. This means identifying potential three-state issues early, structuring investments and operations in a way that minimizes unsynchronized taxing claims, and where possible, seeking advance agreements or clarifications from tax authorities. In contentious cases, it also means being prepared to invoke the MAP to alleviate double taxation after the fact.

Triangular taxation issues underscore that in international tax, some of the most costly mistakes are those of omission - failing to see that a third jurisdiction's tax has slipped through the cracks of treaty coverage.

Sources

- OECD Model Tax Convention (2017) and Commentary (especially Commentary on Articles 4, 23, and 24).

- OECD Committee on Fiscal Affairs, Triangular Cases (1992 Report) (background to 1992 updates of OECD Model).

- IBFD, Triangular Cases: The Application of Bilateral Income Tax Treaties (Emily Fett, 2021).