THE TIGER GLOBAL JUDGMENT: WHEN TREATY ENTITLEMENT YIELDS TO GAAR

Excerpt

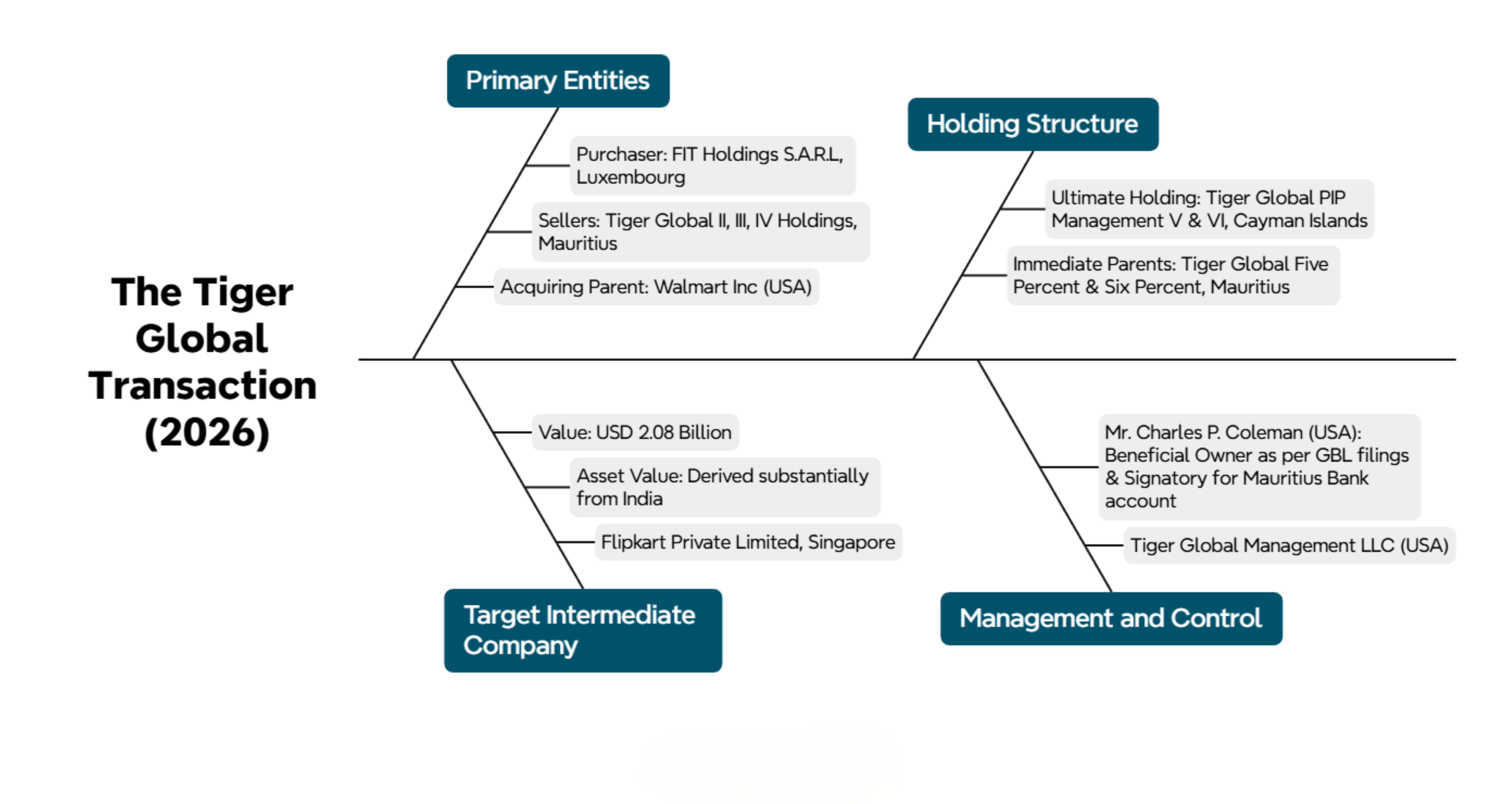

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Tiger Global must be understood in the context of its earlier decisions in Azadi Bachao Andolan and Vodafone, which together chart the evolution of India’s treaty jurisprudence. This analysis traces that evolution from form-based treaty entitlement toward a statute-d...

The significance of Tiger Global, a recent judgement by the Indian Supreme Court, lies not merely in its outcome, but in how it completes a longer judicial transition that began with Azadi and continued through Vodafone.

Glossary

| Assessee | Taxpayer |

| Azadi | Union of India v. Azadi Bachao Andolan (2004) 263 ITR 706 (SC) |

| CBDT | Central Board of Direct Taxes |

| DTAA | Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement |

| GAAR | General Anti-Avoidance Rule |

| LOB | Limitation of Benefits |

| MLI | Multilateral Instrument |

| PPT | Principal Purpose Test |

| Tiger Global | Tiger Global International II Holdings & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors. (SC 262/263/264 of 2026) |

| TRC | Tax Residency Certificate |

| Vodafone | Vodafone International Holdings B.V. v. Union of India (2012) 341 ITR 1 (SC) |

Read together, these cases reveal a clear movement from form-based treaty entitlement toward a statute-driven, substance-oriented anti-avoidance regime.

This blog is meant to cover all the practical implications arising from the Supreme Court decision in Tiger Global, but does not cover:

- The potential areas of challenge should this decision be sent for a review to a larger bench.

- Certain remarks in the judgement and the repercussions of the same. For instance,

- Para 18: an indirect sale of shares would not, at the threshold, fall within the treaty protection contemplated under Article 13;

- Para 49: only if the assessee is liable to pay tax in Mauritius, he can derive benefit under Article 13(c) as amended.

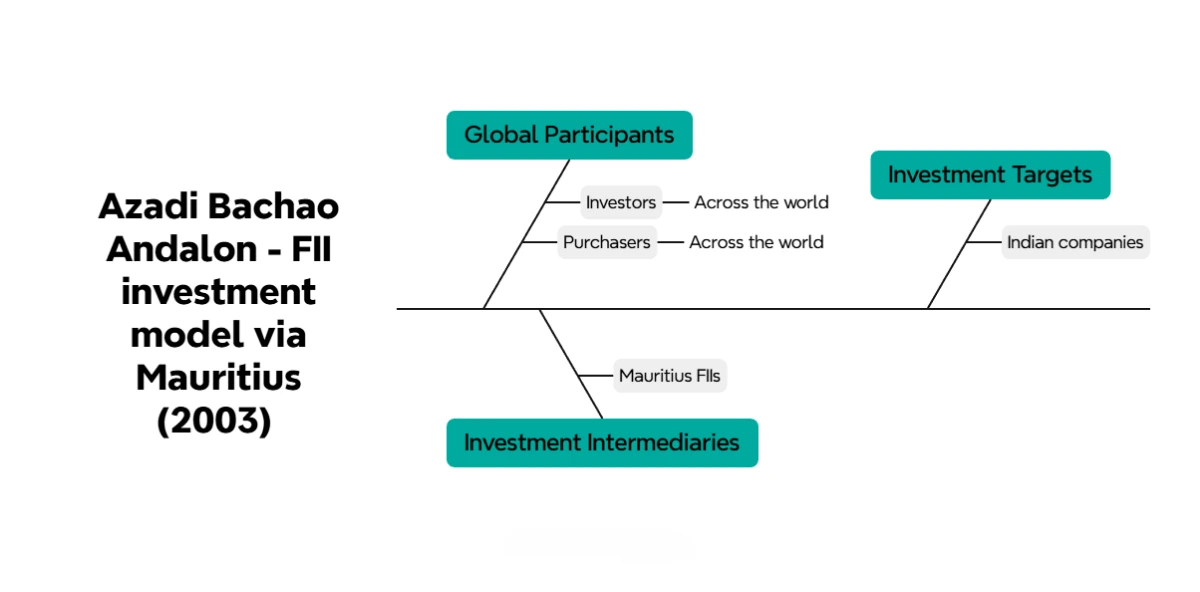

1. Treaty shopping: from tolerated planning to high-risk strategy

From Azadi to Tiger Global: Treaty shopping under judicial scrutiny

Aspect | Azadi / Vodafone (pre-GAAR) | Tiger Global (post-GAAR) |

|---|---|---|

View of treaty shopping | Not per se objectionable if treaty conditions were satisfied | Actively scrutinised where arrangements lack commercial purpose |

Role of intermediary entities | Generally respected unless shown to be a sham | May be disregarded if functioning as conduits |

Focus of inquiry | Legal residence and treaty entitlement | Commercial substance and principal purpose |

Judicial tolerance | High, absent clear abuse | Significantly reduced under GAAR |

Going forward, investors can expect much less tolerance for treaty-shopping arrangements. India has asserted its tax sovereignty to deny benefits to conduit entities with no real business purpose. Tax authorities (and courts) will probe substance over form, a holding company inserted merely for tax savings is likely to be looked through.

Thus, structures that previously passed muster under Azadi may be scrutinized under GAAR and modern treaty anti-abuse provisions.

Foreign investors should ensure genuine commercial substance in intermediate jurisdictions; merely routing investment through a low-tax jurisdiction without economic activity there will invite challenge.

In essence, what was once a common tax planning strategy, now carries significant risk under India’s evolving anti-avoidance regime.

2. TRC: necessary, but no longer sufficient

From Azadi to Tiger Global: The changing role of the Tax Residency Certificate

Aspect | Azadi Bachao Andolan | Vodafone | Tiger |

|---|---|---|---|

Status of TRC | TRC treated as conclusive evidence of residence for treaty purposes | TRC relevant but not decisive; form respected unless sham is shown | TRC is a minimum statutory requirement, not conclusive |

Power of tax officer to question | No enquiry permitted into residence or beneficial ownership once a valid TRC is produced | Limited enquiry permitted to examine whether the transaction is a sham or colourable device | Wide enquiry permitted under GAAR into purpose, substance, and commercial rationale |

Scope of scrutiny | Confined strictly to formal treaty entitlement | Narrow, fact-specific scrutiny focused on genuineness of the transaction | Holistic scrutiny, including purpose, substance, and avoidance |

Role of CBDT circulars | Circulars (e.g. Circular 789) treated as binding and determinative | Circulars respected but cannot override statute or judicial scrutiny | Circulars subordinate to GAAR and statutory anti-avoidance rules |

Practical position for taxpayer | High certainty once TRC is obtained | Conditional certainty; exposed only if sham is alleged |

In the post-Tiger Global landscape, a TRC should be viewed as a baseline condition for invoking treaty relief, not a standalone guarantee of getting it.

Taxpayers should continue to obtain TRCs as a matter of hygiene, but be prepared for scrutiny that goes beyond the certificate. In practice, the Indian Revenue is more likely to test whether the TRC is supported by real indicia of residence and substance, such as decision-making, management presence, offices, employees, and operational activity. Where an offshore entity looks like a “paper” resident, a TRC is unlikely to carry the day against a GAAR-style challenge that frames the structure as tax-motivated and lacking commercial substance.

The practical takeaway is straightforward: TRC is necessary, but not conclusive. Multinationals should design and document offshore holding and investment platforms so that the residency claim is reinforced by economic reality, not merely evidenced by a certificate.

3. Substance over form and the normalisation of look-through

From form to transparency in abusive arrangements

Aspect | Azadi / Vodafone | Tiger Global |

|---|---|---|

Corporate separateness | Strongly respected | Conditional on substance |

Look-through approach | Rejected absent sham or statute | Permitted where GAAR applies |

Risk for holding companies | Low if legally compliant | High if commercially hollow |

This shift reflects the Court’s movement from a form-based regime in Azadi, where legal form prevailed subject only to a narrow sham exception, to a cautious recognition of substance in Vodafone, and finally to a GAAR-driven, substance-based enquiry in Tiger Global. In this progression, substance increasingly informs not merely the outcome, but the very framework within which treaty entitlement is assessed.

Going forward, one can expect tax authorities to routinely “lift the veil” in cases of suspected treaty abuse. Treaty benefits are unlikely to be available where the claiming entity is no more than a shell. Courts and tax authorities are expected to examine whether the entity is the real beneficial owner of the income and whether it exercises meaningful control over the investment. Factors such as where strategic and commercial decisions are taken, where capital is sourced, and what risks are actually borne will assume central importance. Where an intermediary lacks independent discretion or business purpose and merely channels income to a parent entity, legal form alone will not protect the arrangement.

Tax professionals must therefore ensure that any intermediate entities have real substance (board meetings, personnel, risk-bearing functions, etc.) to withstand beneficial ownership challenges. In summary, form-alone is not enough: future disputes will be decided by the underlying substance (who truly earns and controls the income).

4. India asserting source taxation strongly

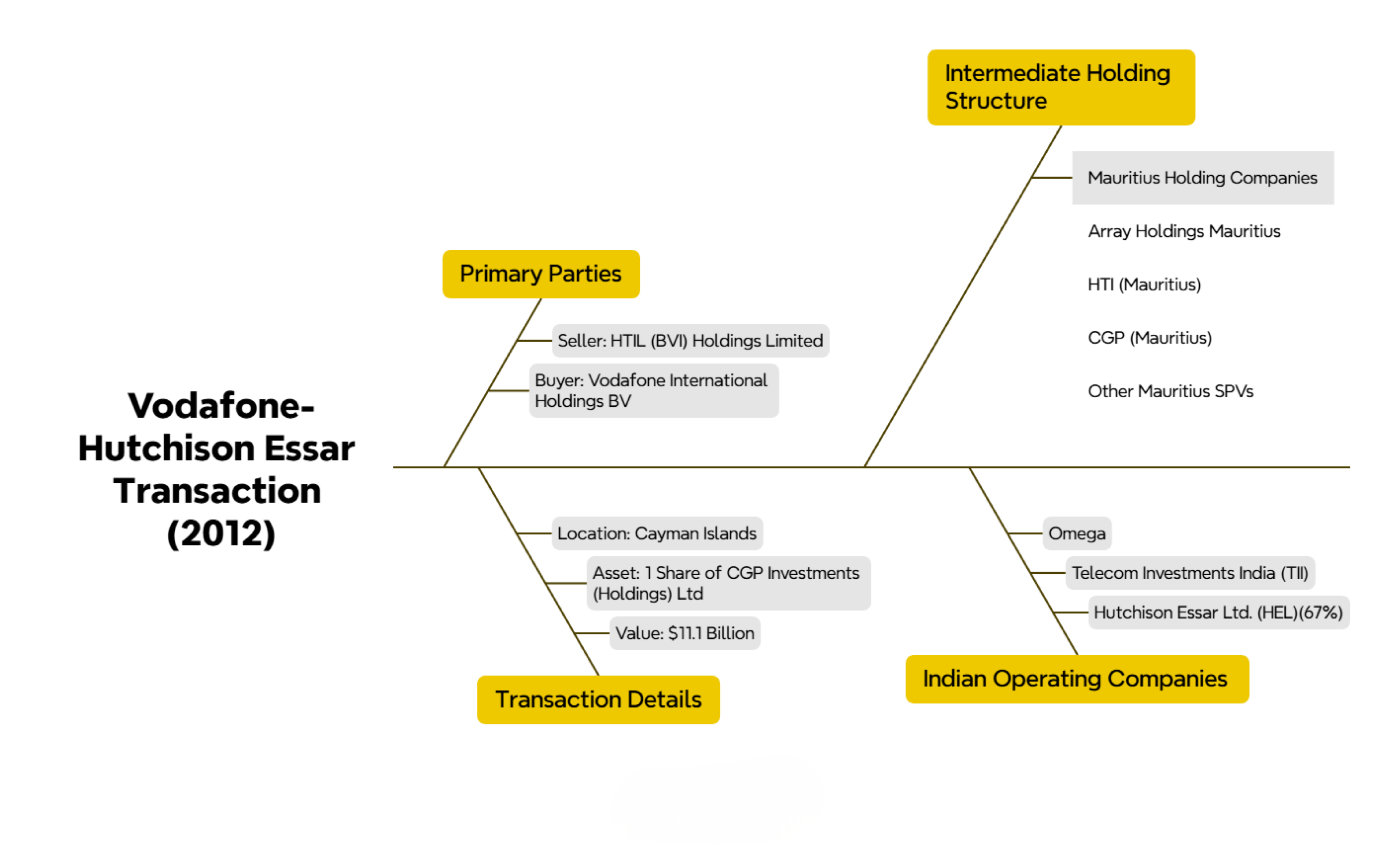

Unlike Azadi and Vodafone, where treaty text often curtailed India’s ability to tax gains at source, Tiger Global reflects judicial acceptance of India’s strengthened source-based taxing rights.

The trajectory indicates that India will tax capital gains arising from Indian assets whenever it has the tools to do so. Treaties are being re-negotiated (or interpreted) to favour source taxation, the 2016 Mauritius protocol ending the blanket exemption serves as a prime example.

For future investments, this means that gains derived from India (directly or indirectly) are likely to fall within India’s tax net, either by treaty design or via GAAR if treaty benefits are misused. Investors can no longer bank on residence-only taxation to avoid Indian tax. The default assumption should be that India will tax exits from Indian investments, unless a treaty benefit clearly applies and the arrangement is bona fide. Moreover, global tax trends (MLI’s Principal Purpose Test, etc.) also bolster source countries’ rights.

In sum, the pendulum has swung toward source-based taxation of capital gains, and structures aimed solely at exploiting residence-based exemptions are at high risk.

5. Treaty provisions interpreted through an anti-abuse lens

The transition from literal treaty interpretation in Azadi and Vodafone to purposive application in Tiger Global is particularly evident in capital gains cases.

The interpretation of Article 13 has shifted from a literal, absolute exemption to a conditional one in practice. Going forward, taxpayers cannot rely on Article 13(4) (or similar articles in other treaties) as an unconditional shield if their transaction is primarily tax-driven. India’s insertion of GAAR and specific DTAA amendments (like Article 13(3A) with LOB conditions) means treaty benefits will be viewed in a purposive light. Capital gains exemptions are no longer iron-clad.

If a structure is clearly used to avoid tax (and would result in double non-taxation), Indian authorities will argue that is beyond the intent of the treaty, invoking domestic law or treaty anti-abuse clauses to tax the income. In practice, this means more certainty for India taxing rights: post-2017 investments are taxed in India by treaty design, and even pre-2017 “grandfathered” gains, where the sale transaction triggering the gains is post-2017, are unsafe if tainted by avoidance.

6. A higher threshold for acceptable tax avoidance

What was once regarded as permissible tax planning under Azadi and Vodafone is now increasingly tested against explicit statutory anti-avoidance thresholds in the post Tiger Global landscape. In effect, the legal boundary between acceptable tax planning and abusive avoidance has shifted, and continues to shift, in a manner that generally strengthens the tax authorities’ position.

Practical implication: tax planning is not dead, but it must be grounded in bona fide commercial substance and be capable of standing on its own without the tax outcome. Tax evasion (illegal concealment of income) remains unequivocally prohibited, but even technically compliant structures that are primarily tax-driven and lack credible non-tax justification face a materially higher risk of being disregarded. Going forward, taxpayers and advisors should lean toward substance and transparency, with contemporaneous documentation of commercial rationale, operational reality, and decision-making. With GAAR now an embedded analytical lens, courts are more likely to view contrived, tax-only arrangements as abusive and to apply a strict, low-tolerance approach.

7. Diminished reliance on administrative circulars

In Azadi, CBDT circulars were afforded substantial deference, displaced only in the narrow case of sham. Vodafone treated them as relevant guidance, but clarified that they do not insulate a transaction from scrutiny where sham is alleged. Tiger Global takes the next step, confirming that administrative guidance must yield to the statute where GAAR is engaged.

As a result, the practical role of CBDT circulars in international tax planning is now more constrained. Earlier, courts often treated circulars as reliable indicators of how treaty positions would be administered. Today, the presence of GAAR (and, where relevant, specific anti-abuse treaty provisions) means statutory standards prevail over executive assurances. Investors should therefore be cautious in relying on legacy “comfort” guidance such as Circular 789: to the extent later legislation introduces additional thresholds, that guidance operates subject to those qualifications. If a circular suggests that “X is sufficient” but GAAR requires a deeper inquiry into purpose, substance, and commerciality, the circular will not foreclose that inquiry.

CBDT will likely continue to issue circulars and clarifications, but their protective value will extend only as far as they remain consistent with the current legal framework. In practice, this shifts the litigation focus. The validity of circulars is largely settled, but disputes will increasingly turn on applicability: the Revenue will argue that a circular cannot be invoked to legitimise abusive facts or to neutralise a GAAR-based challenge.

The bottom line: circulars remain useful in genuine, commercially grounded cases, but they do not operate as a shield against GAAR. Administrative guidance can inform risk assessment and compliance posture, but it cannot be treated as a guarantee where the arrangement is fundamentally tax-driven.

8. Anti-avoidance as a statutory, not judicial, exercise

From judge-made restraint to legislative mandate

Aspect | Azadi / Vodafone | Tiger Global |

|---|---|---|

Nature of anti-avoidance | Judicially developed and narrowly applied | Statutory (GAAR-driven) |

Judicial posture | High restraint absent legislation | Willing enforcement of legislative intent |

Analytical framework | Form and treaty text first | Integrated treaty + GAAR analysis |

The progression across these cases underscores a structural shift in India’s anti-avoidance jurisprudence: from predominantly judge-made doctrines to a legislature-defined regime. GAAR now supplies the principal analytical framework for evaluating avoidance, and courts appear willing to apply it with real rigor. As a result, taxpayers should not assume that legacy precedents such as Azadi and Vodafone will neutralise aggressive structures, those decisions were delivered in a pre-GAAR environment and, in many cases, under treaty texts that did not contain modern anti-abuse provisions.

For litigation, the centre of gravity is also changing. Submissions anchored solely in legal form, or a literal reading of treaty language, will carry less weight where the overall arrangement appears contrived. Judicial attention is increasingly likely to move to the anti-abuse overlay, whether GAAR domestically or PPT (and similar treaty-based tests) at the treaty level. Treaty interpretation, accordingly, is expected to become more purposive, aligned with the object and purpose of preventing abuse and evasion, not merely eliminating double taxation.

A practical way to frame the new landscape is a three-tier inquiry:

- Treaty entitlement: Does the treaty, on its terms, grant the claimed benefit?

- Treaty anti-abuse filter: If yes, do treaty anti-abuse provisions (for example, LOB or PPT) deny the benefit on the facts?

- Domestic anti-avoidance overlay: Even if treaty relief is otherwise available, do GAAR or domestic “substance” doctrines apply to deny the benefit?

The direction of travel is toward integrated anti-avoidance analysis. Treaty interpretation will not occur in isolation, it will operate alongside an active domestic GAAR toolkit. Tax advisors should adapt accordingly: build commercial substance that can be evidenced, document non-tax drivers contemporaneously, and treat GAAR (and treaty anti-abuse clauses) as planning constraints from day one, not as litigation afterthoughts.

9. Burden of proof shifts under GAAR

A procedural inversion in tax disputes

Aspect | Azadi / Vodafone | Tiger Global |

|---|---|---|

Who bears the onus | Revenue | Taxpayer, once GAAR is invoked |

Starting presumption | Transaction presumed valid | Presumption of impermissible avoidance under Section 96(2) |

Taxpayer's role | Defensive | Affirmative justification required |

Planning certainty | Relatively high | Significantly reduced |

The movement from Azadi and Vodafone to Tiger Global reflects a fundamental change in how Indian judiciary approaches tax avoidance. In the earlier regime, the Revenue had to prove that a transaction was a sham or abusive, and taxpayers could largely rely on legal form and treaty language unless the tax authorities discharged this heavy burden. Section 96(2) alters this balance. Once GAAR is invoked, the law presumes that the arrangement is an impermissible avoidance arrangement, and the taxpayer must rebut that presumption by demonstrating genuine commercial purpose and economic substance.

This shift makes tax disputes materially harder for taxpayers in practice. Proving intent and purpose is inherently more difficult than defending legal form. Taxpayers must now produce detailed contemporaneous documentation, explain complex commercial decisions often made years earlier, and justify why tax benefits were not a main driver of the structure. Any gaps, inconsistencies, or post-fact explanations can work against the taxpayer. In effect, uncertainty is introduced at the planning stage itself, because even a legally valid structure may later be challenged if its commercial rationale is not clearly demonstrable.

Importantly, the presumption under Section 96(2) is not conclusive; it is a rebuttable (prima facie) presumption. The taxpayer is given an opportunity to disprove tax avoidance by showing that the arrangement has sufficient substance and was not primarily entered into for obtaining a tax benefit. However, the practical reality is that once GAAR is triggered, the evidentiary burden is substantial, and successfully rebutting the presumption is far more demanding than the pre-GAAR standard where the Revenue carried the primary onus throughout.

Closing observations

Read together, Azadi, Vodafone, and Tiger Global trace a clear arc in India’s treaty jurisprudence. Azadi operated in a world where administrative assurances and formal entitlement carried significant weight, subject mainly to a narrow sham carve-out. Vodafone reinforced that treaty planning is not inherently suspect, but insisted that form must be tested against facts, commercial reality, and the limits of “look-through” arguments. Tiger Global sits in the post-GAAR environment and confirms the modern position: treaty benefits are not evaluated in isolation, they are evaluated through an integrated anti-avoidance lens in which statutory standards and purpose-based scrutiny can override earlier comfort derived from circulars or form-driven structuring.

The practical shift is not that tax planning is prohibited, but that the burden of credibility has moved. Treaty entitlement is no longer a purely textual exercise; it is a combined inquiry into substance, purpose, and consistency with the current statutory framework, including GAAR and treaty anti-abuse provisions such as PPT or LOB where applicable. For taxpayers, the core risk is not technical non-compliance, it is a misalignment between legal architecture and commercial reality. The durable lesson from this trilogy is straightforward: structures that reflect genuine business decisions can still access treaty protection, but arrangements that appear engineered primarily for tax outcomes will increasingly be filtered out, not by judge-made doctrine alone, but by the legislature’s anti-avoidance toolkit and a judiciary prepared to use it.