THE DOUBLE IRISH WITH A DUTCH SANDWICH

A LANDMARK IN INTERNATIONAL TAX AVOIDANCE AND ITS ROLE IN GLOBAL REFORM

Excerpt

The Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich was a widely used international tax planning structure, adopted mainly by U.S. technology and pharmaceutical companies from the late 1980s until its closure in 2020. It leveraged Ireland's residency rules, intellectual property licensing, and Dutch treaty be...

Introduction

Among the numerous tax planning strategies developed over the past half century, few have achieved the notoriety of the "Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich". Originating in the late 1980s and widely used until the 2010s, this arrangement allowed primarily USA-based technology and pharmaceutical multinationals to channel billions in profits to low- or no-tax jurisdictions. In doing so, it helped corporations achieve effective tax rates far below statutory levels, sometimes fractions of a percent.

More than just an accounting manoeuvre, the strategy became emblematic of aggressive tax avoidance. It illustrated how mismatches between national tax systems, coupled with creative exploitation of treaties and directives, could create "stateless income" untaxed anywhere in the world. Its widespread adoption drew unprecedented scrutiny from policymakers, academics, and civil society, ultimately becoming one of the most important catalysts for the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting ("BEPS") initiative launched in 2013.

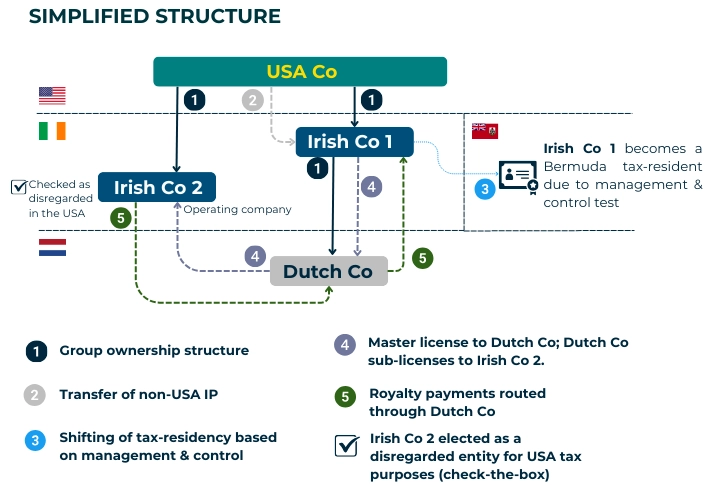

I. Mechanics

The Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich relied on four tightly interlinked components that worked in unison to channel profits away from high-tax jurisdictions. This structure effectively created a funnel, moving income from operating markets into entities located in low or no-tax havens. By carefully exploiting mismatches in tax-residency rules, royalty payments, and treaty provisions, the structure enabled companies to move income seamlessly across borders.

STEP I: Establishing Irish subsidiaries

Irish Co. 1: Incorporated in Ireland but managed and controlled from a tax haven (commonly Bermuda). Under Ireland's pre-2015 rules, tax-residency depended on management and control, not incorporation. Thus, Irish Co. 1 was deemed Bermuda-resident and outside the scope of Irish tax. The USA, meanwhile, treated it as a foreign corporation, deferring tax until repatriation.

Irish Co. 2: Incorporated and tax-resident in Ireland, responsible for European sales, distribution, or services.

This dual structure created a split: one Irish company with a tax-residency in Bermuda (tax haven) for tax purposes, and another, which is the tax-resident in Ireland, bearing only minimal taxable income.

STEP II: Intellectual Property licensing

The USA parent company transferred valuable IP to Irish Co. 1, typically at a low historic cost. Irish Co. 1 then granted a master license to Dutch Co, which in turn sub-licensed the IP to Irish Co. 2 in return for substantial royalty payments. These royalties were deliberately structured to strip out nearly all of Irish Co. 2's profits.

Consequently, even though Irish Co. 2 generated revenues that could run into billions, it reported only minimal taxable income in Ireland.

STEP III: The Dutch sandwich

Any direct royalty payments from Irish Co. 2 to Irish Co. 1 would have triggered Irish withholding tax of up to 20%. To circumvent this, the royalties were first routed through a Dutch affiliate (thanks to the EU Interest and Royalties Directive and the Ireland–Netherlands tax treaty, no withholding tax applied on payments from Ireland to the Netherlands).

At the time, Dutch domestic tax law did not impose withholding tax on outbound royalty payments. As a result, once royalties reached the Dutch affiliate, they could be passed on to Bermuda without an additional tax charge.

In effect, the Dutch entity acted as a tax-neutral conduit, ensuring profits flowed offshore untaxed.

STEP IV: Offshore accumulation

The royalties ultimately flowed to Irish Co. 1, which was treated as Bermuda tax-resident. Given Bermuda's 0% corporate tax rate, these profits accumulated offshore without local taxation.

At the same time, the USA "check-the-box" rules allowed Irish Co. 2 to be disregarded for USA tax purposes, so its royalty payments to Irish Co. 1 were not recognized in the USA tax system.

The combined effect was indefinite deferral of USA tax and no taxation elsewhere.

II. Historical use and Notable Examples

The Double Irish gained wide traction across IP-driven industries during the 1990s and 2000s, and by 2010 it had become a cornerstone of the tax planning strategies used by major Silicon Valley companies. Offshore earnings of USA based multinationals swelled to unprecedented levels, with Fortune 500 firms collectively holding about $2.6 trillion offshore by 2017, much of it attributable to arrangements of this kind.

Apple

Apple's deployment of the Double Irish structure became a global flashpoint. Two Irish-incorporated companies, managed from the USA, claimed tax-residency in neither Ireland nor the USA.

Between 2003 and 2014, Apple's effective tax rate on European profits plummeted from roughly 1% to just 0.005%. In 2016, the European Commission ruled that Ireland had granted Apple unlawful State aid and ordered recovery of €13 billion plus interest.

That ruling was ultimately upheld by the EU's highest court in 2024, cementing Apple's arrangement as one of the most striking examples of aggressive tax avoidance.

Google used the scheme until 2020. In 2017 alone, it moved nearly €20 billion through a Dutch affiliate to Bermuda, achieving single-digit effective rates.

Dutch filings showed minimal local taxation: €3.4 million on €13.6 million profit, despite billions transiting.

Facing reforms in Ireland and USA tax changes, Google announced the termination of the arrangement, consolidating IP licensing in the USA.

Other firms and Variants

Microsoft, Facebook, and major pharmaceutical groups also relied on the structure. When Ireland closed the loophole to new entrants in 2015 and to legacy users by 2020, companies experimented with alternatives.

The Single Malt used treaties with Malta to replicate double non-taxation.

The Green Jersey leveraged Irish capital allowances for intangibles to offset profits domestically.

Both faced pushback:

Ireland and Malta quashed the Single Malt in 2019.

The Green Jersey remains available, but since 2017 its use has been restricted by an 80% cap on allowances, leaving at least 20% of profits taxable in Ireland.

The Single Malt emerged after Ireland announced the closure of the Double Irish (to new users from 2015, with legacy users phased out by 2020). Tax planners sought new stateless-income tools and identified treaty mismatches offering a workaround.

It relied on an Irish-incorporated entity that was "neither tax-resident in Ireland nor in the treaty partner country" (e.g., Malta or the UAE), using Ireland's management-and-control rules and treaty definitions to become resident nowhere for tax purposes.

That same entity, despite being resident nowhere, qualified under tax treaties (e.g., Ireland–Malta) to receive payments without triggering withholding taxes, effectively replicating the Double Irish's offshore carve-out in a simpler form.

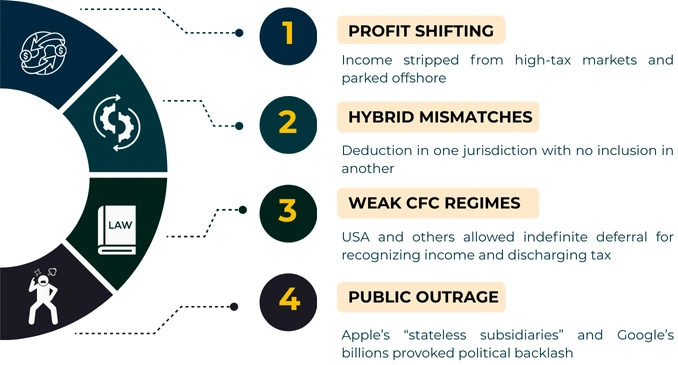

III. Catalyst for BEPS Reform and Policy Discourse

By the early 2010s, the Double Irish had become shorthand for aggressive tax avoidance. Its prominence in political debate and media investigations forced policymakers to act.

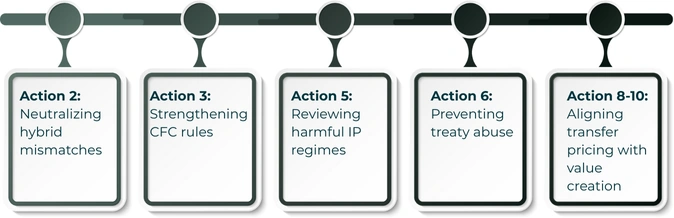

IV. Influence on BEPS

The OECD/G20 BEPS Project, launched in 2013, directly targeted the mechanisms the Double Irish exploited. Relevant Actions included:

The Double Irish, though never cited in legislation by name, was repeatedly referenced in hearings, speeches, and policy papers - emerging as the defining symbol, the very "poster child," of the global BEPS debate.

V. Global Responses and Comparative Stances

a. Ireland and the MLI

Ireland reformed its residency rules in 2015, requiring all Irish-incorporated companies to be tax-resident in Ireland (with a transition period until 2020), eventually ending the "stateless" company model. Ireland also signed the Multilateral Instrument ("MLI"), incorporating the Principal Purpose Test ("PPT") into treaties to curb treaty shopping. The Single Malt loophole with Malta was closed in 2019; similar risks with other partners, such as the UAE, have been addressed.

b. GCC countries

The Gulf Cooperation Council ("GCC"), long home to low-tax regimes, could have served as replacement havens. Ireland's treaty with the UAE was identified as vulnerable. However, GCC states joined the BEPS Inclusive Framework and signed the MLI.

The UAE introduced a 9% federal corporate tax in 2023 and committed to the 15% minimum tax. Saudi Arabia and Qatar strengthened anti-abuse clauses in treaties. While maintaining investment-friendly zones, GCC countries are aligning with BEPS standards and conduit benefits are expected to be neutralized by Pillar II top-up taxes.

c. Other countries

- India has been one of the most aggressive BEPS adopters, introducing GAAR in 2017, enforcing POEM rules, expanding the equalisation levy, tightening transfer pricing, and embedding PPT through early MLI ratification.

- The United Kingdom tackled avoidance with the Diverted Profits Tax in 2015, followed by anti-hybrid rules in 2017 and PPT clauses through the MLI, combining strong domestic measures with international cooperation while still offering incentives like the patent box.

- Singapore aligned early with BEPS by reforming its IP regimes under the nexus approach, requiring real substance for tax incentives, signing the MLI with PPT clauses, and committing to implement Pillar II in 2025.

VI. Phase out and Legacy

By 2020, the Double Irish was effectively extinct. Companies adapted in various ways:

Google and others onshored IP to the USA after the 2017 tax reforms reduced incentives for offshore holding.

Single Malt and Green Jersey variants emerged but were curtailed by treaty updates and domestic reforms.

Some pursued corporate inversions, but tightened USA rules diminished appeal.

VII. Long-Term Impact

Structural Reform

The BEPS package, MLI, and now BEPS 2.0's Pillars I and II directly address the issues exposed. Pillar One reallocates taxing rights to markets, while Pillar II ensures a minimum tax of 15%. Had such rules existed earlier, Apple's 0.005% rate in Ireland would have triggered a top-up tax elsewhere.

Focus on Substance

Authorities now demand alignment between profits and Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection, and Exploitation ("DEMPE") functions. Country-by-country reporting increases transparency. IP licensing arrangements face closer scrutiny.

For Ireland, closing the Double Irish marked a shift from haven perception to compliant hub. Its 12.5% rate, EU access, and skilled workforce continue to attract investment, demonstrating that credibility and stability can substitute for loopholes.

Conclusion

The Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich was a masterclass in exploiting mismatched rules, but its very success ensured its demise. By allowing multinationals to pay almost no tax on vast global profits, it crystallized the urgency of reform and ushered in the BEPS era.

The global response has been sweeping: treaties carry anti-abuse clauses, domestic laws embed anti-hybrid rules and GAAR, and Pillar II sets a 15% floor. The scope for stateless income has narrowed, even as planners search for new avenues.

With over 140 jurisdictions in the Inclusive Framework, the global minimum tax is now a coordinated reality. The Double Irish's legacy is both cautionary and instructive: it showcases the ingenuity of planners and the need for vigilance, and it proves that international cooperation can close gaps and restore fairness.

Its demise marks not just the end of a structure, but the beginning of a more resilient, cooperative international tax order.